|

|

Home | Switchboard | Unix Administration | Red Hat | TCP/IP Networks | Neoliberalism | Toxic Managers |

| (slightly skeptical) Educational society promoting "Back to basics" movement against IT overcomplexity and bastardization of classic Unix | |||||||

The coronavirus crisis has put scientific expertise back in the political driving seat. After years of undermining by populists, the urgency of the situation means chief medical officers and central bankers are now calling the shots. Which means technocracy. At the same time previous cult figures of technocracy are under file and a lot of popular resentment against neoliberalism is projected on them. for example much like Lloyd Blankfein (vampire Squid head honcho) in the past, Bill Gates found himself under fire.

Technocracy seems to be back with ugly face of Fauci .

Beginning in 2008, neoliberal ideology began to unravel: the global financial crisis dealt a blow to neoclassical economic expertise, and the 2016 events devastated the authority of pollsters and pundits. The experts had failed us.

But now, under the extraordinary conditions in which we find ourselves, most Western states have been given over to a high-handed epidemiological technocracy.

The liberal press is not-so-subtly pleased by this situation, quite satisfied to declare the present a “time for experts” and to remind us that “the crisis has reinforced the value of mainstream media.”

The establishment, in particular its liberal wing—that is, parties of the broad center, civil servants, NGOs, the academy, the media—did not react very well to the challenges of COVID-19. For many, it felt like an inexplicable and unconscionable turn of events; the populists were winning.

Since 2016 the most outrageous conspiracy theories like Russiagate were finding a home amidst a social stratum that sees itself as the moral and intellectual guardian of society. This is a reaction of technocracy on the crisis of neoliberalism.

Rachel Maddow pretended the Cold War never ended and ranted about subversive foreign agents, rather like the sort of tinpot dictator she would otherwise admonish. This nostalgia for an extremely recent (and rather mediocre) neoliberal past found risible objects of longing.

This inability on the part of a complacent liberal establishment to accept, explain and respond to political change became so widespread as to require labelling. ‘Trump Derangement Syndrome’ seemed insufficient: after all, paranoya about fake news was tooed in the ciris of neoliberal and thw loss of legimay of the current neoliberal elite.

The people reacting with cries Russiagate and "fake news" to the events of 2016 were the same who had allowed regional inequalities to grow, opportunistically played with immigration to please multinationals, and maintained sadistic labor policies.

Instead of understanding that this time have gone, neoliberal establishments across the West indulged into unhinged fantasies of imminent fascist takeover and right wing conspiracies.

Technocracy’s End-of-Life Rally – Damage

‘Neoliberal Order Breakdown Syndrome’ (NOBS) to describe the psychotic reaction to the fracturing of the neoliberal order, that world in which political decision-making would take its cue from experts rather than popular pressures and demands. For someone like Tony Blair, a neoliberal through and through, the post-2016 world was a “populist nightmare”—as he called the 2019 faceoff between Boris Johnson and Jeremy Corbyn. Further to the left (where ‘neoliberal’ is understandably a slur), political change also proved difficult to handle: the idea that “progressives” would not be the immediate beneficiaries of the breakdown was unthinkable. But so it proved. Rather than offer self-criticism over UK Labour’s missteps, journalist Paul Mason lashed out over the 2019 election result, spitefully calling it “a victory of the old over the young, racists over people of colour, selfishness over the planet.”

NOBS embraces a range of different symptoms. The incredulity and denial of political change was followed by a lack of belief in political causation. If the Democrats lost the rust belt, then surely Obama’s economic policies were at fault? No, it must be something else… maybe the deplorables’ inherent racism? (Never mind that in key counties, many had voted for Obama before switching to Trump in 2016). This incuriousness about what motivated political change, and why voters might have broken with liberalism, led many to reach for cognitive or informational theories. Surely it was the mind-control techniques of Cambridge Analytica or Putin’s bots that did it? And if that didn’t prove satisfactory, the liberal establishment could always play the victim. The well-heeled and well-educated—who now largely vote for center-left and liberal parties—were, we learned, the real unfortunates. Here came the #Resistance.

Was this all a short-lived spasm, one that will be forgotten after the COVID crisis wreaks its havoc? A few months ago the British commentator Will Hutton was suggesting Boris Johnson was a fascist. Now he celebrates Johnson’s rather banal recognition that ‘we live in a society’, and eagerly awaits further anti-pandemic action from the Prime Minister. As the role of the state grows, the demand from progressives is now merely for more quarantine, and quicker. If NOBS is no longer symptomatic, could it be that the pandemic, and its seeming vindication of expert-led politics, have put the professional-managerial classes at ease?

Liberals would never come out and admit that they actually wanted this world of emergency measures, states of exceptions and draconian lockdowns, but the inverse proportion of cases of NOBS and COVID suggests otherwise. Could the same highly educated ‘progressive neoliberals’ whose heads spun in 2016—and continued spinning for the past few years—really feel more at home now, in 2020?

Evidence shows that people in the center of the political spectrum are more authoritarian and less wedded to democracy and liberal institutions than either those on the left or the right. Liberal Hollywood has served us up dark dreams of pandemic and lockdown for quite a while now. If it’s true that the dystopias we dream up are the ones we secretly desire, then is our exceptional situation not the one centrists craved? If this sounds like an outrageous proposition, consider whose authority is being redeemed at this moment. Professionals and specialists are being listened to. Expertise has a direct pipeline to power. Flouters of quarantine—be they errant fun-seekers or Trumpian protesters—can be shouted at and even shopped to the police, by those armed with the right knowledge and sense of urgency of the moment. Evidence-based moral certitude is finally at hand.

So has Neoliberal Order Breakdown Syndrome been cured by the virus? This seems unlikely, so profound and universal were these pathologies. We might instead consider the patient to be experiencing ‘terminal lucidity’—the clarity that sufferers regain just before death. In other words, this might be a mere end-of-life rally for technocracy.

The global revolt against political establishments, rooted in a profound lack of legitimacy and distrust of elites, will not evaporate. Medical professionals consistently score towards the top of the trust charts, so it might be natural that, in a pandemic, we would see a return of trust to politics, as long as the authority for making political decisions is deferred to medical experts.

But it is worth recalling that experts cannot rule directly, because they are divided as to analyses, models and courses of action. Politicians are discovering that ‘The Science’ isn’t as settled as they thought, and scientists are just as ‘political’ as anyone. The scientists, for their part, are disgruntled by the realization that politicians are hiding behind the evidence, in a play to avoid political responsibility.

So it’s not as easy as to say, ‘put the experts in charge’. Which epidemiological model’s assumptions are best? Priorities, values and interests need to be mobilized in order to adjudicate, and this is an intensely political process. Does your epidemiological model assume a free market in the provision of personal protective equipment or a state-directed allocation of resources? Does it assume people will stay at home because their jobs and wages are guaranteed? In the UK, scientists did not initially push for lockdown, believing it was not politically feasible.

The strains against this technocratic revival are already being felt. Protest thus far has been confined to middle-class, right-wing rebels against the lockdown, outraged that they cannot play golf or get a haircut. But what happens when the working class refuses to be the victim? Appealing to the supposed virtues of the ‘scientifically mandated’ lockdown—really, a white-collar quarantine—will not suffice.

It is worth recalling that popular distrust of ‘experts’ was never about expertise as such. The problem was the veto power of those who wield self-serving knowledge over the rest of us, and over all other values and principles. That was the source of antagonism. Who will bear the brunt if larger bodies of citizens begin to call BS on that veto power?

Contrary to the intentions of liberal technocracy boosters, science itself may end up taking the flack. When politicians and intellectuals misleadingly hold up ‘The Science’ as writ—rather than treating science as an open-ended process of discovery—they create unrealistic expectations as to how consolidated that knowledge is, and how capable we are of acting on it. Technocracy and its advocates, in seeking to enthrone evidence as the guide to politics, unwittingly erode the authority of science by articulating it to narrow political imperatives. Future cries to ‘listen to the science’ may sadly fall on deaf ears.

But it is not just outmoded liberal centrists who are falling into this trap. The Left has largely given itself over to cheerleading the lockdowns too. Mass quarantines may well prove to be a lamentable necessity; or they may be shown to have been a grave misstep. What we do already know is that they were the fruit of a panicked response. When we uphold with moral certitude the continued need for lockdown, we distract from governments’ lack of preparation and implementation of pandemic responses, and unwittingly serve the narrow interests of liberals. The shortage of personal protective equipment and the absence of testing and tracing regimes are damning; governments must be held to account. Would left-wing energies, then, not be better served fighting layoffs and lost incomes, defending civil liberties, and fighting for appropriate protection for essential workers—rather than carrying water for technocracy?

This world-historic crisis is an opportunity to fundamentally alter inequalities of wealth and power. Failing to do that because you don’t want to appear to be in accordance with the right-wing denialists is myopic. Soon, elites will need to provide for a resumption of the conditions for capital accumulation in a drastically changed world. This really is the end of the End of History. A form of state capitalism is emerging, by iteration and experimentation rather than by design. Will it be authoritarian or democratic? Will it be universalist or exclusionary? To try to lay low and let the pandemic storm blow over, all the while urging everyone else to seek shelter, is to abandon the crisis to the powers that be. Neoliberalism is ending, but that does not mean we will suddenly get to have nice things.

For liberals living in the vain hope that this pandemus ex machina might resuscitate evidence-based policy, now might be a good opportunity to embrace political change and rediscover leadership through persuasion, rather than through scientific diktat. This is the only way liberals will be able to guarantee whatever values they hold dear—be it tolerance or rationality or individualism. Judging by centrism’s recent record, though, it’s likely that the liberal establishment will abandon itself again to nervous breakdown once the full unfolding of this crisis is laid bare.

|

|

Switchboard | ||||

| Latest | |||||

| Past week | |||||

| Past month | |||||

OCTOBER 14, 2019fb tw mail Print

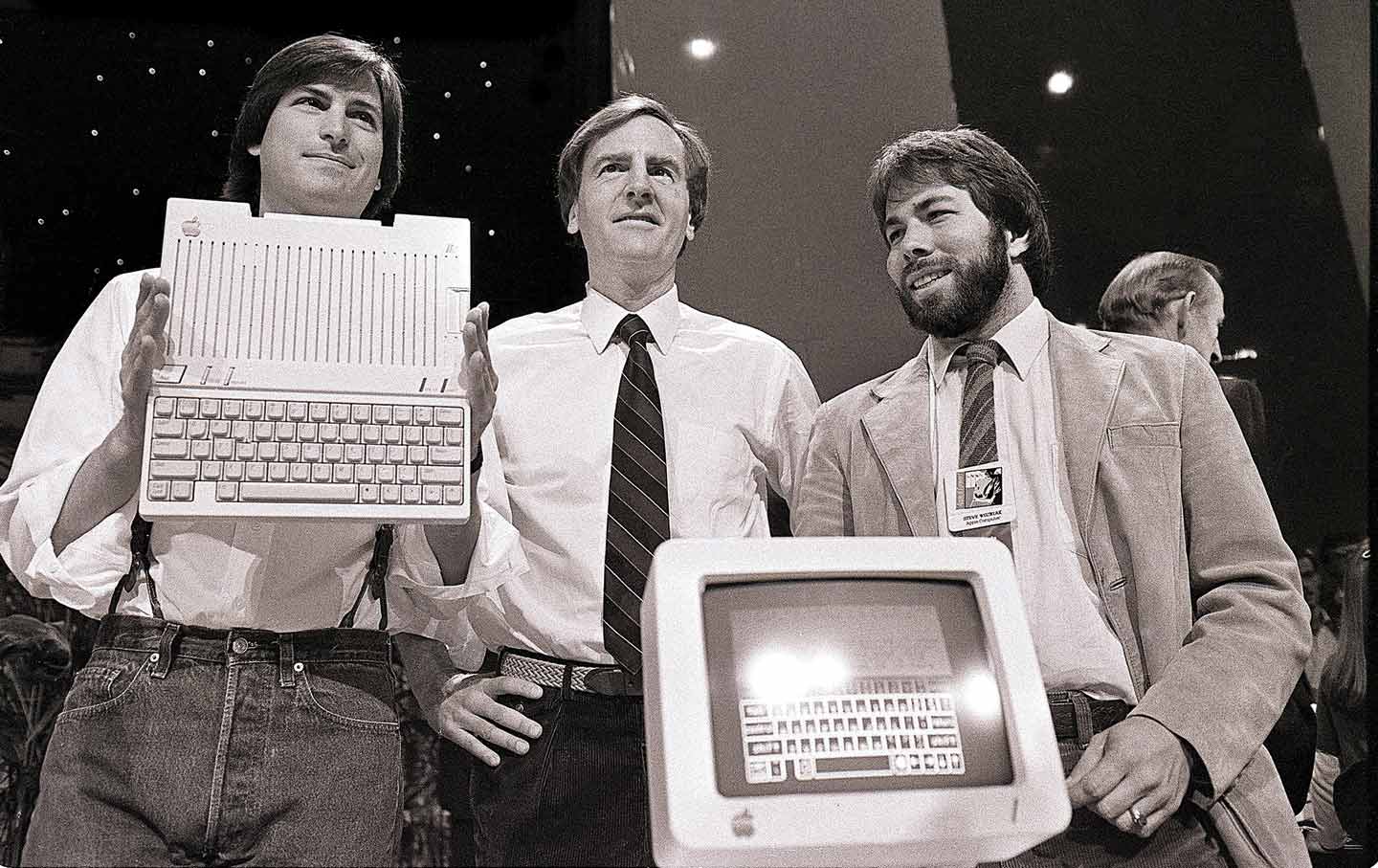

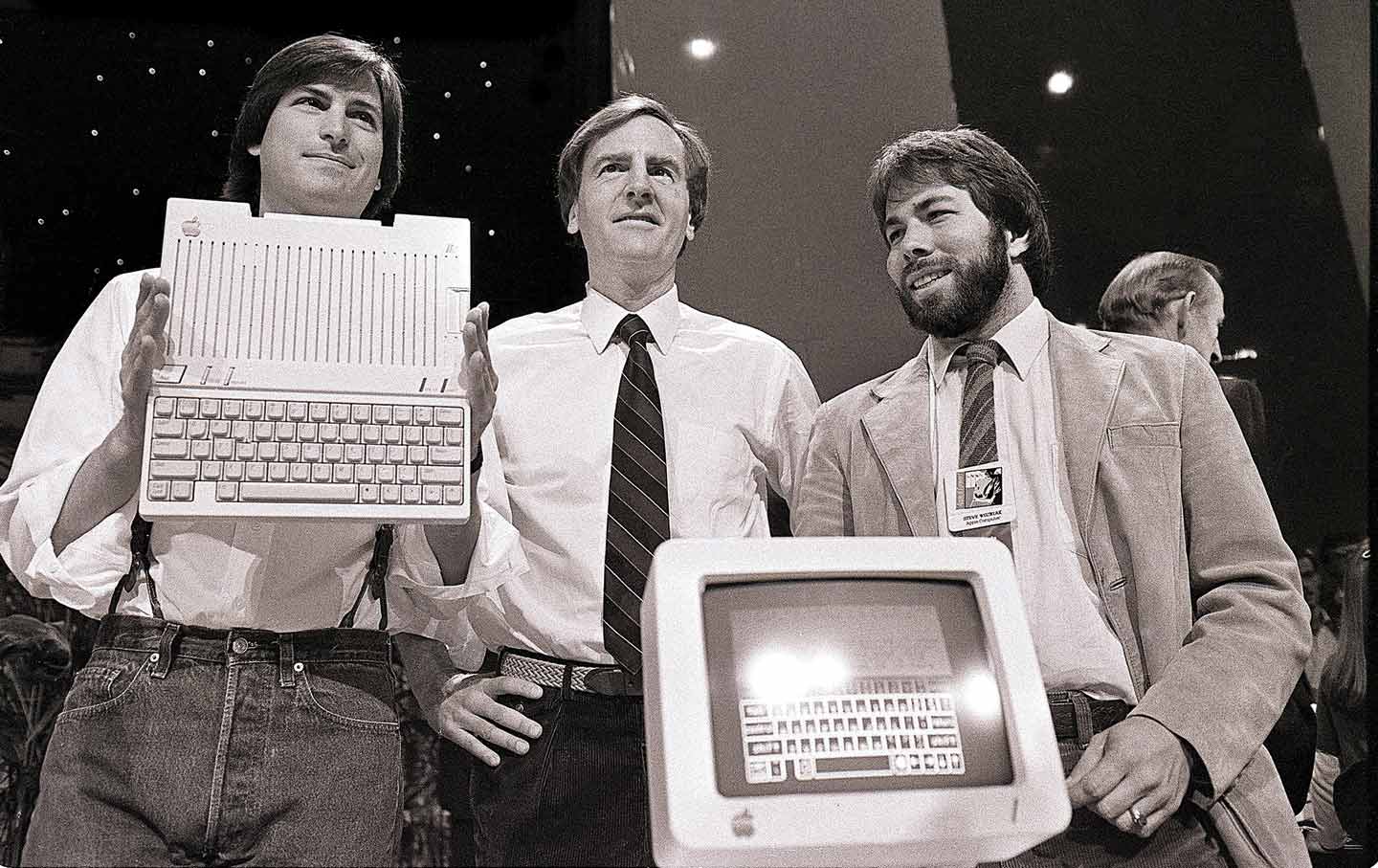

Steve Jobs, John Sculley, and Steve Wozniak, 1984. Steve Jobs, John Sculley, and Steve Wozniak, 1984. O ne of Apple cofounder Steve Jobs's most audacious marketing triumphs is rarely mentioned in the paeans to his genius that remain a staple of business content farms. In 1982, Jobs offered to donate a computer to every K–12 school in America, provided Congress pass a bill giving Apple substantial tax write-offs for the donations. When he arrived in Washington, DC, to lobby for what became known as the Apple Bill, the 28-year-old CEO looked "more like a summer intern than the head of a $600-million-a-year corporation," according to Steve Jobs, John Sculley, and Steve Wozniak, 1984. Steve Jobs, John Sculley, and Steve Wozniak, 1984. O ne of Apple cofounder Steve Jobs's most audacious marketing triumphs is rarely mentioned in the paeans to his genius that remain a staple of business content farms. In 1982, Jobs offered to donate a computer to every K–12 school in America, provided Congress pass a bill giving Apple substantial tax write-offs for the donations. When he arrived in Washington, DC, to lobby for what became known as the Apple Bill, the 28-year-old CEO looked "more like a summer intern than the head of a $600-million-a-year corporation," according to O ne of Apple cofounder Steve Jobs's most audacious marketing triumphs is rarely mentioned in the paeans to his genius that remain a staple of business content farms. In 1982, Jobs offered to donate a computer to every K–12 school in America, provided Congress pass a bill giving Apple substantial tax write-offs for the donations. When he arrived in Washington, DC, to lobby for what became known as the Apple Bill, the 28-year-old CEO looked "more like a summer intern than the head of a $600-million-a-year corporation," according to O ne of Apple cofounder Steve Jobs's most audacious marketing triumphs is rarely mentioned in the paeans to his genius that remain a staple of business content farms. In 1982, Jobs offered to donate a computer to every K–12 school in America, provided Congress pass a bill giving Apple substantial tax write-offs for the donations. When he arrived in Washington, DC, to lobby for what became known as the Apple Bill, the 28-year-old CEO looked "more like a summer intern than the head of a $600-million-a-year corporation," according to The Washington Post , but he already showed signs of his famous arrogance. He barraged the legislators with white papers and proclaimed that they "would be crazy not to take us up on this." Jobs knew the strength of his hand: A mania for computer literacy was sweeping the nation as an answer to the competitive threats of globalization and the reescalation of the Cold War's technology and space races. Yet even as preparing students for the Information Age became a national priority, the Reagan era's budget cuts meant that few schools could afford a brand-new $2,400 Apple II computer.

Steve Jobs, John Sculley, and Steve Wozniak, 1984. Steve Jobs, John Sculley, and Steve Wozniak, 1984. O ne of Apple cofounder Steve Jobs's most audacious marketing triumphs is rarely mentioned in the paeans to his genius that remain a staple of business content farms. In 1982, Jobs offered to donate a computer to every K–12 school in America, provided Congress pass a bill giving Apple substantial tax write-offs for the donations. When he arrived in Washington, DC, to lobby for what became known as the Apple Bill, the 28-year-old CEO looked "more like a summer intern than the head of a $600-million-a-year corporation," according to Steve Jobs, John Sculley, and Steve Wozniak, 1984. Steve Jobs, John Sculley, and Steve Wozniak, 1984. O ne of Apple cofounder Steve Jobs's most audacious marketing triumphs is rarely mentioned in the paeans to his genius that remain a staple of business content farms. In 1982, Jobs offered to donate a computer to every K–12 school in America, provided Congress pass a bill giving Apple substantial tax write-offs for the donations. When he arrived in Washington, DC, to lobby for what became known as the Apple Bill, the 28-year-old CEO looked "more like a summer intern than the head of a $600-million-a-year corporation," according to O ne of Apple cofounder Steve Jobs's most audacious marketing triumphs is rarely mentioned in the paeans to his genius that remain a staple of business content farms. In 1982, Jobs offered to donate a computer to every K–12 school in America, provided Congress pass a bill giving Apple substantial tax write-offs for the donations. When he arrived in Washington, DC, to lobby for what became known as the Apple Bill, the 28-year-old CEO looked "more like a summer intern than the head of a $600-million-a-year corporation," according to O ne of Apple cofounder Steve Jobs's most audacious marketing triumphs is rarely mentioned in the paeans to his genius that remain a staple of business content farms. In 1982, Jobs offered to donate a computer to every K–12 school in America, provided Congress pass a bill giving Apple substantial tax write-offs for the donations. When he arrived in Washington, DC, to lobby for what became known as the Apple Bill, the 28-year-old CEO looked "more like a summer intern than the head of a $600-million-a-year corporation," according to The Washington Post , but he already showed signs of his famous arrogance. He barraged the legislators with white papers and proclaimed that they "would be crazy not to take us up on this." Jobs knew the strength of his hand: A mania for computer literacy was sweeping the nation as an answer to the competitive threats of globalization and the reescalation of the Cold War's technology and space races. Yet even as preparing students for the Information Age became a national priority, the Reagan era's budget cuts meant that few schools could afford a brand-new $2,400 Apple II computer. BOOKS IN REVIEW( Sep 19, 2020 , www.thenation.com )

OCTOBER 14, 2019fb tw mail Print

Steve Jobs, John Sculley, and Steve Wozniak, 1984. Steve Jobs, John Sculley, and Steve Wozniak, 1984. O ne of Apple cofounder Steve Jobs's most audacious marketing triumphs is rarely mentioned in the paeans to his genius that remain a staple of business content farms. In 1982, Jobs offered to donate a computer to every K–12 school in America, provided Congress pass a bill giving Apple substantial tax write-offs for the donations. When he arrived in Washington, DC, to lobby for what became known as the Apple Bill, the 28-year-old CEO looked "more like a summer intern than the head of a $600-million-a-year corporation," according to Steve Jobs, John Sculley, and Steve Wozniak, 1984. Steve Jobs, John Sculley, and Steve Wozniak, 1984. O ne of Apple cofounder Steve Jobs's most audacious marketing triumphs is rarely mentioned in the paeans to his genius that remain a staple of business content farms. In 1982, Jobs offered to donate a computer to every K–12 school in America, provided Congress pass a bill giving Apple substantial tax write-offs for the donations. When he arrived in Washington, DC, to lobby for what became known as the Apple Bill, the 28-year-old CEO looked "more like a summer intern than the head of a $600-million-a-year corporation," according to O ne of Apple cofounder Steve Jobs's most audacious marketing triumphs is rarely mentioned in the paeans to his genius that remain a staple of business content farms. In 1982, Jobs offered to donate a computer to every K–12 school in America, provided Congress pass a bill giving Apple substantial tax write-offs for the donations. When he arrived in Washington, DC, to lobby for what became known as the Apple Bill, the 28-year-old CEO looked "more like a summer intern than the head of a $600-million-a-year corporation," according to O ne of Apple cofounder Steve Jobs's most audacious marketing triumphs is rarely mentioned in the paeans to his genius that remain a staple of business content farms. In 1982, Jobs offered to donate a computer to every K–12 school in America, provided Congress pass a bill giving Apple substantial tax write-offs for the donations. When he arrived in Washington, DC, to lobby for what became known as the Apple Bill, the 28-year-old CEO looked "more like a summer intern than the head of a $600-million-a-year corporation," according to The Washington Post , but he already showed signs of his famous arrogance. He barraged the legislators with white papers and proclaimed that they "would be crazy not to take us up on this." Jobs knew the strength of his hand: A mania for computer literacy was sweeping the nation as an answer to the competitive threats of globalization and the reescalation of the Cold War's technology and space races. Yet even as preparing students for the Information Age became a national priority, the Reagan era's budget cuts meant that few schools could afford a brand-new $2,400 Apple II computer.

Steve Jobs, John Sculley, and Steve Wozniak, 1984. Steve Jobs, John Sculley, and Steve Wozniak, 1984. O ne of Apple cofounder Steve Jobs's most audacious marketing triumphs is rarely mentioned in the paeans to his genius that remain a staple of business content farms. In 1982, Jobs offered to donate a computer to every K–12 school in America, provided Congress pass a bill giving Apple substantial tax write-offs for the donations. When he arrived in Washington, DC, to lobby for what became known as the Apple Bill, the 28-year-old CEO looked "more like a summer intern than the head of a $600-million-a-year corporation," according to Steve Jobs, John Sculley, and Steve Wozniak, 1984. Steve Jobs, John Sculley, and Steve Wozniak, 1984. O ne of Apple cofounder Steve Jobs's most audacious marketing triumphs is rarely mentioned in the paeans to his genius that remain a staple of business content farms. In 1982, Jobs offered to donate a computer to every K–12 school in America, provided Congress pass a bill giving Apple substantial tax write-offs for the donations. When he arrived in Washington, DC, to lobby for what became known as the Apple Bill, the 28-year-old CEO looked "more like a summer intern than the head of a $600-million-a-year corporation," according to O ne of Apple cofounder Steve Jobs's most audacious marketing triumphs is rarely mentioned in the paeans to his genius that remain a staple of business content farms. In 1982, Jobs offered to donate a computer to every K–12 school in America, provided Congress pass a bill giving Apple substantial tax write-offs for the donations. When he arrived in Washington, DC, to lobby for what became known as the Apple Bill, the 28-year-old CEO looked "more like a summer intern than the head of a $600-million-a-year corporation," according to O ne of Apple cofounder Steve Jobs's most audacious marketing triumphs is rarely mentioned in the paeans to his genius that remain a staple of business content farms. In 1982, Jobs offered to donate a computer to every K–12 school in America, provided Congress pass a bill giving Apple substantial tax write-offs for the donations. When he arrived in Washington, DC, to lobby for what became known as the Apple Bill, the 28-year-old CEO looked "more like a summer intern than the head of a $600-million-a-year corporation," according to The Washington Post , but he already showed signs of his famous arrogance. He barraged the legislators with white papers and proclaimed that they "would be crazy not to take us up on this." Jobs knew the strength of his hand: A mania for computer literacy was sweeping the nation as an answer to the competitive threats of globalization and the reescalation of the Cold War's technology and space races. Yet even as preparing students for the Information Age became a national priority, the Reagan era's budget cuts meant that few schools could afford a brand-new $2,400 Apple II computer. BOOKS IN REVIEW

Sep 19, 2020 | www.thenation.com

By Margaret O'Mara

The Apple Bill passed the House overwhelmingly but then died in the Senate after a bureaucratic snafu for which Jobs forever blamed Republican Senator Bob Dole of Kansas, then chair of the Finance Committee. Yet all was not lost: A similar bill passed in California, and Apple flooded its home state with almost 10,000 computers. Apple's success in California gave it a leg up in the lucrative education market as states around the country began to computerize their classrooms. But education was not radically transformed, unless you count a spike in The Oregon Trail –related deaths from dysentery. If anything, those who have studied the rapid introduction of computers into classrooms in the 1980s and '90s tend to conclude that it exacerbated inequities. Elite students and schools zoomed smoothly into cyberspace, while poorer schools fell further behind, bogged down by a lack of training and resources.

A young, charismatic geek hawks his wares using bold promises of social progress but actually makes things worse and gets extremely rich in the process -- today it is easy to see the story of the Apple Bill as a stand-in for the history of the digital revolution as a whole. The growing concern about the role that technology plays in our lives and society is fueled in no small part by a growing realization that we have been duped. We were told that computerizing everything would lead to greater prosperity, personal empowerment, collective understanding, even the ability to transcend the limits of the physical realm and create a big, beautiful global brain made out of electrons. Instead, our extreme dependence on technology seems to have mainly enriched and empowered a handful of tech companies at the expense of everyone else. The panic over Facebook's impact on democracy sparked by Donald Trump's election in a haze of fake news and Russian bots felt like the national version of the personal anxiety that seizes many of us when we find ourselves snapping away from our phone for what seems like the 1,000th time in an hour and contemplating how our lives are being stolen by a screen. We are stuck in a really bad system.

Top Articles Countdown to Election: 52 Days READ MORE READ MORE READ MORE READ MORE READ MORE READ MORE SKIP AD This realization has led to a justifiable anger and derision aimed at the architects of this system. Silicon Valley executives and engineers are taken to task every week in the op-ed pages of our largest newspapers. We are told that their irresponsibility and greed have undermined our freedom and degraded our democratic institutions. While it is gratifying to see tech billionaires get a (very small) portion of their comeuppance, we often forget that until very recently, Silicon Valley was hailed by almost everyone as creating the path toward a brilliant future. Perhaps we should pause and contemplate how this situation came to be, lest we make the same mistakes again. The story of how Silicon Valley ended up at the center of the American dream in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, as well as the ambiguous reality behind its own techno-utopian dreams, is the subject of Margaret O'Mara's sweeping new history, The Code: Silicon Valley and the Remaking of America . In it, she puts Silicon Valley into the context of a larger story about postwar America's economic and social transformations, highlighting its connections with the mainstream rather than the cultural quirks and business practices that set it apart. The Code urges us to consider Silicon Valley's shortcomings as America's shortcomings, even if it fails to interrogate them as deeply as our current crisis -- and the role that technology played in bringing it about -- seems to warrant.

S ilicon Valley entered the public consciousness in the 1970s as something of a charmed place. The first recorded mention of Silicon Valley was in a 1971 article by a writer for a technology newspaper reporting on the region's semiconductor industry, which was booming despite the economic doldrums that had descended on most of the country. As the Rust Belt foundered and Detroit crumbled, Silicon Valley soared to heights barely conveyed by the metrics that O'Mara rattles off in the opening pages of The Code : "Three billion smartphones. Two billion social media users. Two trillion-dollar companies" and "the richest people in the history of humanity." Many people have attempted to divine the secret of Silicon Valley's success. The consensus became that the Valley had pioneered a form of quicksilver entrepreneurialism perfectly suited to the Information Age. It was fast, flexible, meritocratic, and open to new ways of doing things. It allowed brilliant young people to turn crazy ideas into world-changing companies practically overnight. Silicon Valley came to represent the innovative power of capitalism freed from the clutches of uptight men in midcentury business suits, bestowed upon the masses by a new, appealing folk hero: the cherub-faced start-up founder hacking away in his dorm room.

The Code both bolsters and revises this story. On the one hand, O'Mara, a historian at the University of Washington, is clearly enamored with tales of entrepreneurial derring-do. From the "traitorous eight" who broke dramatically from the Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory in 1957 to start Fairchild Semiconductor and create the modern silicon transistor to the well-documented story of Facebook's founding, the major milestones of Silicon Valley history are told in heroic terms that can seem gratingly out of touch, given what we know about how it all turned out. In her portrayal of Silicon Valley's tech titans, O'Mara emphasizes virtuous qualities like determination, ingenuity, and humanistic concern, while hints of darker motives are studiously ignored. We learn that a "visionary and relentless" Jeff Bezos continued to drive a beat-up Honda Accord even as he became a billionaire, but his reported remark to an Amazon sales team that they ought to treat small publishers the way a lion treats a sickly gazelle is apparently not deemed worthy of the historical record. But at the same time, O'Mara helps us understand why Silicon Valley's economic dominance can't be chalked up solely to the grit and smarts of entrepreneurs battling it out in the free market. At every stage of its development, she shows how the booming tech industry was aided and abetted by a wide swath of American society both inside and outside the Valley. Marketing gurus shaped the tech companies' images, educators evangelized for technology in schools, best-selling futurists preached personalized tech as a means toward personal liberation. What emerges in The Code is less the story of a tribe of misfits working against the grain than the simultaneous alignment of the country's political, cultural, and technical elites around the view that Silicon Valley held the key to the future.

Above all, O'Mara highlights the profound role that the US government played in Silicon Valley's rise. At the end of World War II, the region was still the sleepy, sun-drenched Santa Clara Valley, home to farms and orchards, an upstart Stanford University, and a scattering of small electronics and aerospace firms. Then came the space and arms races, given new urgency in 1957 with the launch of Sputnik, which suggested a serious Soviet advantage. Millions of dollars in government funding flooded technology companies and universities around the country. An outsize portion went to Northern California's burgeoning tech industry, thanks in large part to Stanford's far-sighted provost Frederick Terman, who reshaped the university into a hub for engineering and the applied sciences.

CURRENT ISSUEView our current issue

Subscribe today and Save up to $129.

Stanford and the surrounding area became a hive of government R&D during these years, as IBM and Lockheed Martin opened local outposts and the first native start-ups hit the ground. While these early companies relied on what O'Mara calls the Valley's "ecosystem" of fresh-faced engineers seeking freedom and sunshine in California, venture capitalists sniffing out a profitable new industry, and lawyers, construction companies, and real estate agents jumping to serve their somewhat quirky ways, she makes it clear that the lifeblood pumping through it all was government money. Fairchild Semiconductor's biggest clients for its new silicon chips were NASA, which put them in the Apollo rockets, and the Defense Department, which stuck them in Minuteman nuclear missiles. The brains of all of today's devices have their origin in the United States' drive to defeat the Soviet Union in the Cold War.

But the role of public funding in the creation of Silicon Valley is not the big government success story a good liberal might be tempted to consider it. As O'Mara points out, during the Cold War American leaders deliberately pushed public funds to private industry rather than government programs because they thought the market was the best way to spur technological progress while avoiding the specter of centralized planning, which had come to smack of communist tyranny. In the years that followed, this belief in the market as the means to achieve the goals of liberal democracy spread to nearly every aspect of life and society, from public education and health care to social justice, solidifying into the creed we now call neoliberalism. As the role of the state was eclipsed by the market, Silicon Valley -- full of brilliant entrepreneurs devising technologies that promised to revolutionize everything they touched -- was well positioned to step into the void.

T he earliest start-up founders hardly seemed eager to assume the mantle of social visionary that their successors, today's flashy celebrity technologists, happily take up. They were buttoned-down engineers who reflected the cool practicality of their major government and corporate clients. As the 1960s wore on, they were increasingly out of touch. Amid the tumult of the civil rights movement and the protests against the Vietnam War, the major concern in Silicon Valley's manicured technology parks was a Johnson-era drop in military spending. The relatively few techies who were political at the time were conservative.

Things started to change in the 1970s. The '60s made a belated arrival in the Valley as a younger generation of geeks steeped in countercultural values began to apply them to the development of computer technology. The weight of Silicon Valley's culture shifted from the conservative suits to long-haired techno-utopians with dreams of radically reorganizing society through technology. This shift was perhaps best embodied by Lee Felsenstein, a former self-described "child radical" who cut his teeth running communications operations for anti-war and civil rights protests before going on to develop the Tom Swift Terminal, one of the earliest personal computers. Felsenstein believed that giving everyday people access to computers could liberate them from the crushing hierarchy of modern industrial society by breaking the monopoly on information held by corporations and government bureaucracies. "To change the rules, change the tools," he liked to say. Whereas Silicon Valley had traditionally developed tools for the Man, these techies wanted to make tools to undermine him. They created a loose-knit network of hobbyist groups, drop-in computer centers, and DIY publications to share knowledge and work toward the ideal of personal liberation through technology. Their dreams seemed increasingly achievable as computers shrank from massive, room-filling mainframes to the smaller-room-filling minicomputers to, finally, in 1975, the first commercially viable personal computer, the Altair.

SUPPORT PROGRESSIVE JOURNALISMIf you like this article, please give today to help fund The Nation 's work.

Yet as O'Mara shows, the techno-utopians did not ultimately constitute such a radical break from the past. While their calls to democratize computing may have echoed Marxist cries to seize the means of production, most were capitalists at heart. To advance the personal computer "revolution," they founded start-ups, trade magazines, and business forums, relying on funding from venture capital funds often with roots in the old money elite. Jobs became the most celebrated entrepreneur of the era by embodying the discordant figures of both the cowboy capitalist and the touchy-feely hippie, an image crafted in large part by the marketing guru Regis McKenna. Silicon Valley soon became an industry that looked a lot like those that had come before. It was nearly as white and male as they were. Its engineers worked soul-crushing hours and blew off steam with boozy pool parties. And its most successful company, Microsoft, clawed its way to the top through ruthless monopolistic tactics.

Perhaps the strongest case against the supposed subversiveness of the personal computer pioneers is how quickly they were embraced by those in power. As profits rose and spectacular IPOs seized headlines throughout the 1980s, Silicon Valley was championed by the rising stars of supply-side economics, who hitched their drive for tax cuts and deregulation to tech's venture-capital-fueled rocket ship. The groundwork was laid in 1978, when the Valley's venture capitalists formed an alliance with the Republicans to kill then-President Jimmy Carter's proposed increase in the capital gains tax. They beta-tested Reaganomics by advancing the dubious argument that millionaires' making slightly less money on their investments might stifle technological innovation by limiting the supply of capital available to start-ups. And they carried the day.

As president, Ronald Reagan doubled down with tax cuts and wild technophilia. In a truly trippy speech to students at Moscow State University in 1988, he hailed the transcendent possibilities of the new economy epitomized by Silicon Valley, predicting a future in which "human innovation increasingly makes physical resources obsolete." Meanwhile, the market-friendly New Democrats embraced the tech industry so enthusiastically that they became known, to their chagrin, as Atari Democrats. The media turned Silicon Valley entrepreneurs into international celebrities with flattering profiles and cover stories -- living proof that the mix of technological innovation, risk taking, corporate social responsibility, and lack of regulation that defined Silicon Valley in the popular imagination was the template for unending growth and prosperity, even in an era of deindustrialization and globalization.

T he near-universal celebration of Silicon Valley as an avatar of free-market capitalism in the 1980s helped ensure that the market would guide the Internet's development in the 1990s, as it became the cutting-edge technology that promised to change everything. The Internet began as an academic resource, first as ARPANET, funded and overseen by the Department of Defense, and later as the National Science Foundation's NSFNET. And while Al Gore didn't invent the Internet, he did spearhead the push to privatize it: As the Clinton administration's "technology czar," he helped develop its landmark National Information Infrastructure (NII) plan, which emphasized the role of private industry and the importance of telecommunications deregulation in constructing America's "information superhighway." Not surprisingly, Gore would later do a little-known turn as a venture capitalist with the prestigious Valley firm Kleiner Perkins, becoming very wealthy in the process. In response to his NII plan, the advocacy group Computer Professionals for Social Responsibility warned of a possible corporate takeover of the Internet. "An imaginative view of the risks of an NII designed without sufficient attention to public-interest needs can be found in the modern genre of dystopian fiction known as 'cyberpunk,'" they wrote. "Cyberpunk novelists depict a world in which a handful of multinational corporations have seized control, not only of the physical world, but of the virtual world of cyberspace." Who can deny that today's commercial Internet has largely fulfilled this cyberpunk nightmare? Someone should ask Gore what he thinks.

Despite offering evidence to the contrary, O'Mara narrates her tale of Silicon Valley's rise as, ultimately, a success story. At the end of the book, we see it as the envy of other states around the country and other countries around the world, an "exuberantly capitalist, slightly anarchic tech ecosystem that had evolved over several generations." Throughout the book, she highlights the many issues that have sparked increasing public consternation with Big Tech of late, from its lack of diversity to its stupendous concentration of wealth, but these are framed in the end as unfortunate side effects of the headlong rush to create a new and brilliant future. She hardly mentions the revelations by the National Security Agency whistle-blower Edward Snowden of the US government's chilling capacity to siphon users' most intimate information from Silicon Valley's platforms and the voraciousness with which it has done so. Nor does she grapple with Uber, which built its multibillion-dollar leviathan on the backs of meagerly paid drivers. The fact that in order to carry out almost anything online we must subject ourselves to a hypercommodified hellscape of targeted advertising and algorithmic sorting does not appear to be a huge cause for concern. But these and many other aspects of our digital landscape have made me wonder if a technical complex born out of Cold War militarism and mainstreamed in a free-market frenzy might not be fundamentally always at odds with human flourishing. O'Mara suggests at the end of her book that Silicon Valley's flaws might be redeemed by a new, more enlightened, and more diverse generation of techies. But haven't we heard this story before?

If there is a larger lesson to learn from The Code , it is that technology cannot be separated from the social and political contexts in which it is created. The major currents in society shape and guide the creation of a system that appears to spring from the minds of its inventors alone. Militarism and unbridled capitalism remain among the most powerful forces in the United States, and to my mind, there is no reason to believe that a new generation of techies might resist them any more effectively than the previous ones. The question of fixing Silicon Valley is inseparable from the question of fixing the system of postwar American capitalism, of which it is perhaps the purest expression. Some believe that the problems we see are bugs that might be fixed with a patch. Others think the code is so bad at its core that a radical rewrite is the only answer. Although The Code was written for people in the first group, it offers an important lesson for those of us in the second: Silicon Valley is as much a symptom as it is a cause of our current crisis. Resisting its bad influence on society will ultimately prove meaningless if we cannot also formulate a vision of a better world -- one with a more humane relationship to technology -- to counteract it. And, alas, there is no app for that. MOST POPULAR

1THE DARK SIDE OF THE CULT OF RUTH BADER GINSBURG

2RUTH BADER GINSBURG'S DYING WISH: DISSENT!

3MAYA MOORE AND JONATHAN IRONS: MORE THAN A LOVE STORY

4IF WE DON'T REFORM THE SUPREME COURT, NOTHING ELSE WILL MATTER

5IS TRUMP PLANNING A COUP D'ÉTAT?

Adrian Chen Adrian Chen is a freelance writer. He is working on a book about Internet culture.

To submit a correction for our consideration, click here.

For Reprints and Permissions, click here. COMMENTS (3) Trending Today

Tommy Chong: Throw Away Your CBD NowTommy Chong

Tommy Chong: Throw Away Your CBD NowTommy Chong Top Rated Holsters - Made in the USAWe The People Holsters

Top Rated Holsters - Made in the USAWe The People Holsters Doing This Before Bed Reverses Gum And Tooth DecayHealthier Patriot

Doing This Before Bed Reverses Gum And Tooth DecayHealthier Patriot

Sep 19, 2020 | www.zerohedge.com

ay_arrow

Doc McGee , 34 minutes ago

A list of some companies too stupid to care about truth or justice.

22 COMPANIES THAT SUPPORT #BLACKLIVESMATTER

- Airbnb

- A16z

- Bumble

- Cisco

- Docusign

- DoorDash

- Eaze

- Etsy

- Grindr

- Grubhub

- IBM

- Matchstick Ventures

- Microsoft

- Niantic

- Peloton

- RobinHood

- Salesforce

- Shopify

- Snap

- Uber

- Techtonic

Google matched content |

Society

Groupthink : Two Party System as Polyarchy : Corruption of Regulators : Bureaucracies : Understanding Micromanagers and Control Freaks : Toxic Managers : Harvard Mafia : Diplomatic Communication : Surviving a Bad Performance Review : Insufficient Retirement Funds as Immanent Problem of Neoliberal Regime : PseudoScience : Who Rules America : Neoliberalism : The Iron Law of Oligarchy : Libertarian Philosophy

Quotes

War and Peace : Skeptical Finance : John Kenneth Galbraith :Talleyrand : Oscar Wilde : Otto Von Bismarck : Keynes : George Carlin : Skeptics : Propaganda : SE quotes : Language Design and Programming Quotes : Random IT-related quotes : Somerset Maugham : Marcus Aurelius : Kurt Vonnegut : Eric Hoffer : Winston Churchill : Napoleon Bonaparte : Ambrose Bierce : Bernard Shaw : Mark Twain Quotes

Bulletin:

Vol 25, No.12 (December, 2013) Rational Fools vs. Efficient Crooks The efficient markets hypothesis : Political Skeptic Bulletin, 2013 : Unemployment Bulletin, 2010 : Vol 23, No.10 (October, 2011) An observation about corporate security departments : Slightly Skeptical Euromaydan Chronicles, June 2014 : Greenspan legacy bulletin, 2008 : Vol 25, No.10 (October, 2013) Cryptolocker Trojan (Win32/Crilock.A) : Vol 25, No.08 (August, 2013) Cloud providers as intelligence collection hubs : Financial Humor Bulletin, 2010 : Inequality Bulletin, 2009 : Financial Humor Bulletin, 2008 : Copyleft Problems Bulletin, 2004 : Financial Humor Bulletin, 2011 : Energy Bulletin, 2010 : Malware Protection Bulletin, 2010 : Vol 26, No.1 (January, 2013) Object-Oriented Cult : Political Skeptic Bulletin, 2011 : Vol 23, No.11 (November, 2011) Softpanorama classification of sysadmin horror stories : Vol 25, No.05 (May, 2013) Corporate bullshit as a communication method : Vol 25, No.06 (June, 2013) A Note on the Relationship of Brooks Law and Conway Law

History:

Fifty glorious years (1950-2000): the triumph of the US computer engineering : Donald Knuth : TAoCP and its Influence of Computer Science : Richard Stallman : Linus Torvalds : Larry Wall : John K. Ousterhout : CTSS : Multix OS Unix History : Unix shell history : VI editor : History of pipes concept : Solaris : MS DOS : Programming Languages History : PL/1 : Simula 67 : C : History of GCC development : Scripting Languages : Perl history : OS History : Mail : DNS : SSH : CPU Instruction Sets : SPARC systems 1987-2006 : Norton Commander : Norton Utilities : Norton Ghost : Frontpage history : Malware Defense History : GNU Screen : OSS early history

Classic books:

The Peter Principle : Parkinson Law : 1984 : The Mythical Man-Month : How to Solve It by George Polya : The Art of Computer Programming : The Elements of Programming Style : The Unix Hater’s Handbook : The Jargon file : The True Believer : Programming Pearls : The Good Soldier Svejk : The Power Elite

Most popular humor pages:

Manifest of the Softpanorama IT Slacker Society : Ten Commandments of the IT Slackers Society : Computer Humor Collection : BSD Logo Story : The Cuckoo's Egg : IT Slang : C++ Humor : ARE YOU A BBS ADDICT? : The Perl Purity Test : Object oriented programmers of all nations : Financial Humor : Financial Humor Bulletin, 2008 : Financial Humor Bulletin, 2010 : The Most Comprehensive Collection of Editor-related Humor : Programming Language Humor : Goldman Sachs related humor : Greenspan humor : C Humor : Scripting Humor : Real Programmers Humor : Web Humor : GPL-related Humor : OFM Humor : Politically Incorrect Humor : IDS Humor : "Linux Sucks" Humor : Russian Musical Humor : Best Russian Programmer Humor : Microsoft plans to buy Catholic Church : Richard Stallman Related Humor : Admin Humor : Perl-related Humor : Linus Torvalds Related humor : PseudoScience Related Humor : Networking Humor : Shell Humor : Financial Humor Bulletin, 2011 : Financial Humor Bulletin, 2012 : Financial Humor Bulletin, 2013 : Java Humor : Software Engineering Humor : Sun Solaris Related Humor : Education Humor : IBM Humor : Assembler-related Humor : VIM Humor : Computer Viruses Humor : Bright tomorrow is rescheduled to a day after tomorrow : Classic Computer Humor

The Last but not Least Technology is dominated by two types of people: those who understand what they do not manage and those who manage what they do not understand ~Archibald Putt. Ph.D

Copyright © 1996-2021 by Softpanorama Society. www.softpanorama.org was initially created as a service to the (now defunct) UN Sustainable Development Networking Programme (SDNP) without any remuneration. This document is an industrial compilation designed and created exclusively for educational use and is distributed under the Softpanorama Content License. Original materials copyright belong to respective owners. Quotes are made for educational purposes only in compliance with the fair use doctrine.

FAIR USE NOTICE This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available to advance understanding of computer science, IT technology, economic, scientific, and social issues. We believe this constitutes a 'fair use' of any such copyrighted material as provided by section 107 of the US Copyright Law according to which such material can be distributed without profit exclusively for research and educational purposes.

This is a Spartan WHYFF (We Help You For Free) site written by people for whom English is not a native language. Grammar and spelling errors should be expected. The site contain some broken links as it develops like a living tree...

|

|

You can use PayPal to to buy a cup of coffee for authors of this site |

Disclaimer:

The statements, views and opinions presented on this web page are those of the author (or referenced source) and are not endorsed by, nor do they necessarily reflect, the opinions of the Softpanorama society. We do not warrant the correctness of the information provided or its fitness for any purpose. The site uses AdSense so you need to be aware of Google privacy policy. You you do not want to be tracked by Google please disable Javascript for this site. This site is perfectly usable without Javascript.

Last modified: September 19, 2020