Modern forms of slavery in the USA

If

you think that slavery disappeared in the USA think again. Slaves now are cheaper than ever and can

generate high economic returns.

Invisible

hand of the market proved to be pretty adept in reproducing slavery. About 100,000 girls

in the U.S. are under the control of a pimp or trafficker, Shared Hope International says. Modern

slavery is very cheap, and Kevin Bales has argued that this has made modern slavery even worse than

that of Atlantic Slave Trade:

If

you think that slavery disappeared in the USA think again. Slaves now are cheaper than ever and can

generate high economic returns.

Invisible

hand of the market proved to be pretty adept in reproducing slavery. About 100,000 girls

in the U.S. are under the control of a pimp or trafficker, Shared Hope International says. Modern

slavery is very cheap, and Kevin Bales has argued that this has made modern slavery even worse than

that of Atlantic Slave Trade:

In the United States before the Civil War, the average slave cost the equivalent of about fifty

thousand dollars. I'm not sure what the average price of a slave is today, but it can't be more than

fifty or sixty dollars.

Such low prices influence how the slaves are treated. Slave owners used to maintain long relationships

with their slaves, but slaveholders no longer have any reason to do so. If you pay just a hundred

dollars for someone, that person is disposable, as far as you are concerned...

And while the price of slaves has gone down, the return on the slaveholder's investment has skyrocketed.

In the antebellum South, slaves brought an average return of about 5 percent. Now bonded agricultural

laborers in India generate more than a 50 percent profit per year for their slaveholders, and a return

of 800 percent is not at all uncommon for holders of sex slaves.

Interview with Kevin Bales, 2001

The practice still continues today in one form or another in every country in the world. From women

forced into prostitution, children and adults forced to work in agriculture, domestic work, or factories

and sweatshops producing goods for global supply chains, entire families forced to work for nothing

to pay off generational debts; or girls forced to marry older men, the illegal practice still blights

contemporary world. It is estimated that 50,000 people are trafficked every year in the United States.

The same is true for the world as a whole (What

is Modern Slavery).

Over the past 15 years, “trafficking in persons” and “human trafficking” have been used as umbrella

terms for activities involved when someone obtains or holds a person in compelled service.The

United States government considers trafficking in persons to include all of the criminal conduct

involved in forced labor and sex trafficking, essentially the conduct involved in reducing or holding

someone in compelled service. Under the Trafficking Victims Protection Act as amended (TVPA) and

consistent with the United Nations Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons,

Especially Women and Children (Palermo Protocol), individuals may be trafficking victims regardless

of whether they once consented, participated in a crime as a direct result of being trafficked, were

transported into the exploitative situation, or were simply born into a state of servitude. Despite

a term that seems to connote movement, at the heart of the phenomenon of trafficking in persons are

the many forms of enslavement, not the activities involved in international transportation.

Forced Labor

Also known as involuntary servitude, forced labor may result when unscrupulous employers exploit

workers made more vulnerable by high rates of unemployment, poverty, crime, discrimination, corruption,

political conflict, or even cultural acceptance of the practice. Immigrants are particularly vulnerable,

but individuals also may be forced into labor in their own countries. Female victims of forced or

bonded labor, especially women and girls in domestic servitude, are often sexually exploited as well.

Sex Trafficking

When an adult is coerced, forced, or deceived into prostitution – or maintained in prostitution

through coercion – that person is a victim of trafficking. All of those involved in recruiting, transporting,

harboring, receiving, or obtaining the person for that purpose have committed a trafficking crime.

Sex trafficking can also occur within debt bondage, as women and girls are forced to continue in

prostitution through the use of unlawful “debt” purportedly incurred through their transportation,

recruitment, or even their crude “sale,” which exploiters insist they must pay off before they can

be free.

It is critical to understand that a person’s initial consent to participate in prostitution is

not legally determinative; if an individual is thereafter held in service through psychological manipulation

or physical force, that person is a trafficking victim and should receive the benefits outlined in

the United Nations’ Palermo Protocol and applicable laws.

Bonded Labor

One form of coercion is the use of a bond, or debt. Often referred to as “bonded labor” or “debt

bondage,” the practice has long been prohibited under U.S. law by its Spanish name, peonage, and

the Palermo Protocol calls for its criminalization as a form of trafficking in persons. Workers around

the world fall victim to debt bondage when traffickers or recruiters unlawfully exploit an initial

debt the worker assumed as part of the terms of employment. Workers may also inherit intergenerational

debt in more traditional systems of bonded labor.

Debt Bondage Among Migrant LaborersAbuses of contracts and hazardous conditions of employment

for migrant laborers do not necessarily constitute human trafficking. However, the burden of illegal

costs and debts on these laborers in the source country, often with the support of labor agencies

and employers in the destination country, can contribute to a situation of debt bondage. This is

often exacerbated when the worker’s status in the country is tied to the employer in the context

of employment-based temporary work programs and there is no effective redress for abuse.

Involuntary Domestic Servitude

A unique form of forced labor is the involuntary servitude of domestic workers, whose workplace

is informal, connected to their off-duty living quarters, and not often shared with other workers.

Such an environment, which often socially isolates domestic workers, is conducive to nonconsensual

exploitation since authorities cannot inspect private property as easily as formal workplaces. Investigators

and service providers report many cases of untreated illnesses and, tragically, widespread sexual

abuse, which in some cases may be symptoms of a situation of involuntary servitude. Ongoing international

efforts seek to ensure that not only that administrative remedies are enforced but also that criminal

penalties are enacted against those who hold others in involuntary domestic servitude.

Forced Child Labor

Most international organizations and national laws recognize that children may legally engage

in certain forms of work. There is a growing consensus, however, that the worst forms of child labor

should be eradicated. The sale and trafficking of children and their entrapment in bonded and forced

labor are among these worst forms of child labor. A child can be a victim of human trafficking regardless

of the location of that exploitation. Indicators of forced labor of a child include situations in

which the child appears to be in the custody of a non-family member who has the child perform work

that financially benefits someone outside the child’s family and does not offer the child the option

of leaving. Anti-trafficking responses should supplement, not replace, traditional actions against

child labor, such as remediation and education. However, when children are enslaved, their abusers

should not escape criminal punishment by virtue of longstanding patters of limited responses to child

labor practices rather than more effective law enforcement action.

Child Soldiers

Child soldiering can be a manifestation of human trafficking where it involves the unlawful recruitment

or use of children—through force, fraud, or coercion—as combatants, or for labor or sexual exploitation

by armed forces. Perpetrators may be government forces, paramilitary organizations, or rebel groups.

Many children are forcibly abducted to be used as combatants. Others are made unlawfully to work

as porters, cooks, guards, servants, messengers, or spies. Young girls can be forced to marry or

have sex with male combatants. Both male and female child soldiers are often sexually abused and

are at high risk of contracting sexually transmitted diseases.

Child Sex Trafficking

According to UNICEF, as many as two million children are subjected to prostitution in the global

commercial sex trade. International covenants and protocols obligate criminalization of the commercial

sexual exploitation of children. The use of children in the commercial sex trade is prohibited under

both U.S. law and the Palermo Protocol as well as by legislation in countries around the world. There

can be no exceptions and no cultural or socioeconomic rationalizations preventing the rescue of children

from sexual servitude. Sex trafficking has devastating consequences for minors, including long-lasting

physical and psychological trauma, disease (including HIV/AIDS), drug addiction, unintended pregnancy,

malnutrition, social ostracism, and death.

To educate yourself further about human trafficking, take our

TIP 101 Training»

Slaves can be an attractive investment because the slave-owner only needs to pay for sustenance and

enforcement. This is sometimes lower than the wage-cost of free labourers, as free workers earn more

than sustenance; in these cases slaves have positive price. When the cost of sustenance and enforcement

exceeds the wage rate, slave-owning would no longer be profitable, and owners would simply release their

slaves. Slaves are thus a more attractive investment in high-wage environments, and environments where

enforcement is cheap, and less attractive in environments where the wage-rate is low and enforcement

is expensive.[9]

Free workers also earn

compensating differentials,

whereby they are paid more for doing unpleasant work. Neither sustenance nor enforcement costs rise

with the unpleasantness of the work, however, so slaves' costs do not rise by the same amount. As such,

slaves are more attractive for unpleasant work, and less for pleasant work. Because the unpleasantness

of the work is not internalised, being born by the slave rather than the owner, it is a

negative externality

and leads to over-use of slaves in these situations.[9]

Modern slavery can be quite profitable[10]

and corrupt governments will tacitly allow it, despite it being outlawed by international treaties such

as

Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery and local laws. Total annual revenues of traffickers

were estimated in 2004 to range from US $5 billion to US $9 billion,[11]

though profits are substantially lower.

... ... ...

Along with migrant slavery, forced prostitution is the form of slavery most often encountered in

wealthy countries such as the United States, in Western Europe, and in the Middle East. It is the primary

form of slavery in Eastern Europe and Southeast Asia, particularly in Moldova and Laos. Many child sex

slaves are trafficked from these areas to the West and Middle East.

Mainly driven by the culture in certain regions, early or forced marriage is a form of slavery that

affects millions of women and girls all over the world. When families cannot support their children,

the daughters are often married off to the males of wealthier, more powerful families. These men are

often significantly older than the girls. The females are forced into lives whose main purpose is to

serve their husbands. This oftentimes fosters an environment for physical, verbal and sexual abuse.

Children comprise the majority of slaves today.[citation needed] Most are domestic workers or work

in cocoa, cotton or fishing industries. Many are trafficked and sexually exploited. In war-torn countries,

children have been kidnapped and sold to political parties to be used as child soldiers. Forced child

labor is the dominant form of slavery in Haiti.

According to

United States

Department of State data, an "estimated 600,000 to 820,000 men, women, and children [are] trafficked

across international borders each year, approximately 70 percent are women and girls and up to 50 percent

are minors. The data also illustrates that the majority of transnational victims are trafficked into

commercial sexual exploitation."[14]

However, "the alarming enslavement of people for purposes of labor exploitation, often in their own

countries, is a form of human trafficking that can be hard to track from afar." It is estimated that

50,000 people are trafficked every year in the United States.[12]

- 20150819 : IA Radio Host Jan Mickelson Enslave Undocumented Immigrants Unless They Leave ( Aug 19, 2015 , Blog Media Matters for America )

- 20150722 : Black Immigrants' Lives Matter Disrupting the Dialogue on Immigrant Detention ( Black Immigrants' Lives Matter Disrupting the Dialogue on Immigrant Detention, Jul 22, 2015 )

- 20141221 : Slavery and Capitalism by Matt Roth ( December 12, 2014 , The Chronicle of Higher Education )

- 20141221 : The American Gulag as the latest form of capitalism by Valentin KATASONOV ( 23.11.2012 , Strategic-Culture.org )

- 20141221 : Slavery in America New Forms of an Old Monster ( Slavery in America New Forms of an Old Monster , )

- 20141221 : conversantlife.com ( conversantlife.com, )

- 20141221 : Volunteers try to dissuade young sex workers on Super Bowl weekend by By Emanuella Grinberg ( February 6, 2010 , CNN.com )

Mickelson,

Who Recently Hosted Walker, Fiorina, Carson, And Santorum, Asked, "What's Wrong With

Slavery?"

Blog ›››

9 hours and 11 minutes ago ››› DANIEL ANGSTER &

SALVATORE COLLELUORI

Iowa

radio host and influential conservative kingmaker Jan Mickelson unveiled an

immigration plan that would make undocumented immigrants who don't leave the country

after an allotted time "property of the state," asking, "What's wrong with slavery?"

when a caller criticized his plan.

On the August 17 edition of his radio show,

Mickelson announced that he had a plan to drive undocumented immigrants out of Iowa

that involved making those who don't leave "property of the state" who are forced

into "compelled labor," like building a wall on the US-Mexican border. Listen

(emphasis added in transcript):

JAN MICKELSON: Now here is what would work. And I was asked by an immigration

open border's activist a couple of weeks ago, how I would get all the illegals

here in the state of Iowa to leave. "Are you going to call the police every time

you find an illegal, are you going to round them up and put them in detention

centers?"

I said, "No you don't have to do any of that stuff."

"Well you going to invite them to leave the country and leave Iowa?"

And I said, "Well, sort of."

"Well how you going to do it, Mickelson? You think you're so smart. How would

you get thousands of illegals to leave Iowa?"

Well, I said, "Well if I wanted to do that I would just put up some signs."

"Well what would the signs say?"

I said, "Well I'd would put them on the end of the highway, on western part of

the interstate system, and I'd put them on the eastern side of the state, right

there on the interstate system, and in the north on the Minnesota border, and on

the south Kansas and Missouri border and I would just say this: 'As of this date'

-- whenever we decide to do this -- 'as of this date, 30--' this is a totally

arbitrary number, '30 to 60 days from now anyone who is in the state of Iowa

that who is not here legally and who cannot demonstrate their legal status to the

satisfaction of the local and state authorities here in the State of Iowa, become

property of the State of Iowa.' So if you are here without our permission, and we

have given you two months to leave, and you're still here, and we find that you're

still here after we we've given you the deadline to leave, then you become

property of the State of Iowa. And we have a job for you. And we start using

compelled labor, the people who are here illegally would therefore be owned by the

state and become an asset of the state rather than a liability and we start

inventing jobs for them to do.

"Well how would you apply that logic to what Donald Trump is trying to do?

Trying to get Mexico to pay for the border and for the wall?"

"Same way. We say, 'Hey, we are not going to make Mexico pay for the wall,

we're going to invite the illegal Mexicans and illegal aliens to build it. If you

have come across the border illegally, again give them another 60-day guideline,

you need to go home and leave this jurisdiction, and if you don't you become

property of the United States, and guess what? You will be building a wall. We

will compel your labor. You would belong to these United States. You show up

without an invitation, you get to be an asset. You get to be a construction

worker. Cool!'

When a caller confronted Mickelson and said his plan amounted to "slavery,"

Mickelson replied, "What's wrong with slavery?" Mickelson told the caller his plan

was "moral," "legal," and "politically doable" and should be modeled after Maricopa

County (Arizona) Sheriff Joe Arpaio's "tent village" (emphasis added in transcript):

MICKELSON: So anyway back to the point. Put up a sign that says at the end of

60 days, if you are not here with our permission, can't prove your legal status,

you become property of the state. And then we start to extort or exploit or

indenture your labor. This is Fred. Good morning Fred.

CALLER: Hey good morning, how are you?

MICKELSON: I'm doing great.

CALLER: Great. Well you caught me--I was up at 4 o'clock this morning, I'm

travelling from Tulsa through Des Moines. I think I'll stop by the state fair to

see Carly and them, but your idea is clever on the face but it sounds an awful lot

like slavery. I don't think - I think it'll go over like a lead balloon.

MICKELSON: No, just read the Constitution, Fred. What does the Constitution say

about slavery?

CALLER: Well didn't we fix that in about 1865?

MICKELSON: Yeah we sure did and I'm willing to live with their fix. What does

the 13th Amendment say?

CALLER: Well you know I don't have my Constitution in front of me and you know

like I say, it sounds like a clever idea and maybe you can make it - put it in

action, but I think the fall out would be so significant. And I, you know --

MICKELSON: What would be the nature of the fall out?

CALLER: Well I think everybody would believe it sounds like slavery?

MICKELSON: Well, what's wrong with slavery?

CALLER: Well we know what's wrong with slavery.

MICKELSON: Well apparently we don't because when we allow millions of people

to come into the country who aren't here legally and people who are here are

indentured to those people to pay their bills, their education of their kids, pay

for their food, their food stamps, their medical bills, in some cases even

subsidize their housing, and somehow the people who own the country, who pay the

bills, pay the taxes, they get indentured to the new people who are not even

supposed to be here. Isn't that a lot like slavery?

CALLER: Well you know, you're singing my song; we're all slaves today the

way the government is growing -

MICKELSON: If that's the case, maybe it's time to reverse the process. Isn't

this a perfectly good time to do that?

CALLER: Well that'll swing the pendulum back in a pretty broad swing and maybe

too far and we may end up swinging back the other way further left than we are

right now. I take it about halfway Jan. I think it's a clever idea, it's worth

throwing out there. It isn't an easy topic -

MICKELSON: No this is pretty simple, actually this is very simple, what my

solution is moral and it's legal. And I can't think - and it's also politically

doable.

CALLER: So are you going to house all these people who have chosen to be

indentured?

MICKELSON: Yes, yes, absolutely in a minimal fashion. We would take a lesson

from Sheriff [Joe] Arpaio down in Arizona. Put up a tent village, we feed and

water these new assets, we give them minimal shelter, minimal nutrition, and offer

them the opportunity to work for the benefit of the taxpayers of the state of

Iowa. All they have to do to avoid servitude is to leave.

CALLER: [laughing] Hey, good luck.

MICKELSON: All right, thank you very much I appreciate it.

CALLER: You bet. You bet.

MICKELSON: You think I'm just pulling your leg. I am not.

Mickelson has a history of making

racially-charged,

anti-immigrant remarks but he also has a

strong pull with conservative caucus voters in Iowa. His influence is so big that

he recently hosted several 2016 GOP candidates on his show, including Carly Fiorina,

Rick Santorum, and Ben Carson during their visits to the Iowa State Fair. After

Mickelson defended his immigrant-slave plan, Gov. Scott Walker (R-WI) appeared on his

show. Not surprisingly, Mickelson's immigration plan didn't come up.

As the Black Lives Matter movement continues to grow, many activists within the

mainstream immigrant rights movement are beginning to acknowledge how their

embrace of the refrain "immigrants are not criminals" and their framing of

immigration as a

"new civil rights movement" have created a damaging immigration narrative

that is largely predicated on anti-Blackness. However, recent attempts to

discuss immigration in a way that is inclusive of the Black immigrant

experience have continued to allow for the erasure of Black immigrants and

collusion with the criminal legal system.

There have been calls not to just

decrease but to

abolish immigrant detention. This is a clear nod to the prison abolition

movement. On its face, employing the language of abolition presents a departure

from the conservative and assimilationist tone that has dominated the

conversation around immigration for years. Still, the

emerging rationale for dismantling the immigrant detention system threatens

to undermine the political vision of prison abolition.

Few topics have animated today's chattering classes more than capitalism. In the wake of the global

economic crisis, the discussion has spanned political boundaries, with conservative newspapers in

Britain and Germany running stories on the "future of capitalism" (as if that were in doubt) and

Korean Marxists analyzing its allegedly self-destructive tendencies. Pope Francis has made capitalism

a central theme of his papacy, while the French economist Thomas Piketty attained rock-star status

with a 700-page book

full of tables and statistics and the succinct but decisively unsexy title Capital in the Twenty-First

Century (Harvard University Press).

With such contemporary drama, historians have taken notice. They observe, quite rightly, that

the world we live in cannot be understood without coming to terms with the long history of capitalism-a

process that has arguably unfolded over more than half a millennium. They are further encouraged

by the all-too-frequent

failings of economists, who have tended to naturalize particular economic arrangements by defining

the "laws" of their development with mathematical precision and preferring short-term over long-term

perspectives. What distinguishes today's historians of capitalism is that they insist on its contingent

nature, tracing how it has changed over time as it has revolutionized societies, technologies, states,

and many if not all facets of life.

Nowhere is this scholarly trend more visible than in the United States. And no issue currently

attracts more attention than the relationship between capitalism and slavery.

If capitalism, as many believe, is about wage labor, markets, contracts, and the rule of law,

and, most important, if it is based on the idea that markets naturally tend toward maximizing human

freedom, then how do we understand slavery's role within it? No other national story raises that

question with quite the same urgency as the history of the United States: The quintessential capitalist

society of our time, it also looks back on long complicity with slavery. But the topic goes well

beyond one nation. The relationship of slavery and capitalism is, in fact, one of the keys to understanding

the origins of the modern world.

For too long, many historians saw no problem in the opposition between capitalism and slavery.

They depicted the history of American capitalism without slavery, and slavery as quintessentially

noncapitalist. Instead of analyzing it as the modern institution that it was, they described it as

premodern: cruel, but marginal to the larger history of capitalist modernity, an unproductive system

that retarded economic growth, an artifact of an earlier world. Slavery was a Southern pathology,

invested in mastery for mastery's sake, supported by fanatics, and finally removed from the world

stage by a costly and bloody war.

Some scholars have always disagree with such accounts. In the 1930s and 1940s, C.L.R. James and

Eric Williams argued for the centrality of slavery to capitalism, though their findings were largely

ignored. Nearly half a century later, two American economists, Stanley L. Engerman and Robert William

Fogel, observed in their controversial book Time on the Cross (Little, Brown, 1974) the

modernity and profitability of slavery in the United States. Now a flurry of books and

conferences are building on those

often unacknowledged foundations. They emphasize the dynamic nature of New World slavery, its modernity,

profitability, expansiveness, and centrality to capitalism in general and to the economic development

of the United States in particular.

The historians Robin Blackburn in England, Rafael Marquese in Brazil, Dale Tomich in the United

States, and Michael Zeuske in Germany led the study of slavery in the Atlantic world. They have now

been joined by a group of mostly younger American historians, like Walter Johnson, Seth Rockman,

Caitlin C. Rosenthal, and Edward E. Baptist looking at the United States.

While their works differ, often significantly, all insist that slavery was a key part of American

capitalism-especially during the 19th century, the moment when the institution became inextricable

from the expansion of modern industry-and to the development of the United States as a whole.

For the first half of the 19th century, slavery was at the core of the American economy. The South

was an economically dynamic part of the nation (for its white citizens); its products not only established

the United States' position in the global economy but also created markets for agricultural and industrial

goods grown and manufactured in New England and the mid-Atlantic states. More than half of the nation's

exports in the first six decades of the 19th century consisted of raw cotton, almost all of it grown

by slaves. In an important book, River of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in the Cotton Kingdom

(Harvard University Press, 2013), Johnson observes that steam engines were more prevalent on the

Mississippi River than in the New England countryside, a telling detail that testifies to the modernity

of slavery. Johnson sees slavery not just as an integral part of American capitalism, but as its

very essence. To slavery, a correspondent from Savannah noted in the publication Southern Cultivator,

"does this country largely-very largely-owe its greatness in commerce, manufactures, and its general

prosperity."

Much of the recent work confirms that 1868 observation, taking us outside the major slaveholding

areas themselves and insisting on the national importance of slavery, all the way up to its abolition

in 1865. In these accounts, slavery was just as present in the counting houses of Lower Manhattan,

the spinning mills of New England, and the workshops of budding manufacturers in the Blackstone Valley

in Massachusetts and Rhode Island as on the plantations in the Yazoo-Mississippi Delta. The slave

economy of the Southern states had ripple effects throughout the entire economy, not just shaping

but dominating it.

Merchants in New York City, Boston, and elsewhere, like the Browns in cotton and the Taylors in

sugar, organized the trade of slave-grown agricultural commodities, accumulating vast riches in the

process. Sometimes the connections to slavery were indirect, but not always: By the 1840s, James

Brown was sitting in his counting house in Lower Manhattan hiring overseers for the slave plantations

that his defaulting creditors had left to him. Since planters needed ever more funds to invest in

land and labor, they drew on global capital markets; without access to the resources of New York

and London, the expansion of slave agriculture in the American South would have been all but impossible.

The profits accumulated through slave labor had a lasting impact. Both the Browns and the Taylors

eventually moved out of commodities and into banking. The Browns created an institution that partially

survives to this day as Brown Brothers, Harriman & Co., while Moses Taylor took charge of the precursor

of Citibank. Some of the 19th century's most important financiers-including the Barings and Rothschilds-were

deeply involved in the "Southern trade," and the profits they accumulated were eventually reinvested

in other sectors of the global economy. As a group of freedmen in Virginia observed in 1867, "our

wives, our children, our husbands, have been sold over and over again to purchase the lands we now

locate upon. … And then didn't we clear the land, and raise the crops of corn, of tobacco, of rice,

of sugar, of every thing. And then didn't the large cities in the North grow up on the cotton and

the sugars and the rice that we made?" Slavery, they understood, was inscribed into the very fabric

of the American economy.

Southern slavery was important to American capitalism in other ways as well. As management scholars

and historians have discovered in recent years, innovations in tabulating the cost and productivity

of labor derived from the world of plantations. They were unusual work sites in that owners enjoyed

nearly complete control over their workers and were thus able to reinvent the labor process and the

accounting for it-a power that no manufacturer enjoyed in the mid-19th century.

As Caitlin Rosenthal has

shown,

slave labor allowed the enslavers to experiment in novel ways with labor control. Edward E. Baptist,

who has studied in great detail the work practices on plantations and emphasized their modernity

in The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of Modern Capitalism (Basic Books),

has gone so far as to

argue that as new methods of labor management entered the repertoire of plantation owners, torture

became widely accepted. Slave plantations, not railroads, were in fact America's first "big business."

Moreover, as Seth Rockman has shown, the slave-dominated economy of the South also constituted

an important market for goods produced by a wide variety of Northern manufacturers and artisans.

Supplying plantations clothing and brooms, plows and fine furniture, Northern businesses dominated

the large market in the South, which itself did not see significant industrialization before the

end of the 19th century.

Further, as all of us learned in school, industrialization in the United States focused at first

largely on cotton manufacturing: the spinning of cotton thread with newfangled machines and eventually

the weaving of that thread with looms powered at first by water and then by steam. The raw material

that went into the factories was grown almost exclusively by slaves. Indeed, the large factories

emerging along the rivers of New England, with their increasing number of wage workers, cannot be

imagined without reliable, ever-increasing supplies of ever-cheaper raw cotton. The Cabots, Lowells,

and Slaters-whatever their opinions on slavery-all profited greatly from the availability of cheap,

slave-grown cotton.

As profits accumulated in the cotton trade, in cotton manufacturing, in cotton growing, and in

supplying Southern markets, many cultural, social, and educational institutions benefited: congregations,

hospitals, universities. Given that the United States in the first half of the 19th century was a

society permeated by slavery and its earnings, it is hardly surprising that institutions that at

first glance seem far removed from the violence of plantation life came to be implicated in slavery

as well.

Craig Steven Wilder has

shown in Ebony

and Ivy: Race, Slavery, and the Troubled History of America's Universities (Bloomsbury, 2013)

how Brown and Harvard Universities, among others, drew donations from merchants involved in the slave

trade, had cotton manufacturers on their boards, trained generations of Southern elites who returned

home to a life of violent mastery, and played central roles in creating the ideological underpinnings

of slavery.

By 1830, one million Americans, most of them enslaved, grew cotton. Raw cotton was the most important

export of the United States, at the center of America's financial flows and emerging modern business

practices, and at the core of its first modern manufacturing industry. As John Brown, a fugitive

slave, observed in 1854: "When the price [of cotton] rises in the English market, the poor slaves

immediately feel the effects, for they are harder driven, and the whip is kept more constantly going."

Just as cotton, and with it slavery, became key to the U.S. economy, it also moved to the center

of the world economy and its most consequential transformations: the creation of a globally interconnected

economy, the Industrial Revolution, the rapid spread of capitalist social relations in many parts

of the world, and the Great Divergence-the moment when a few parts of the world became quite suddenly

much richer than every other part.

... ... ...

It is for this reason that most history has been framed within the borders of modern states. In

recent years, however, some historians have tried to think beyond such frameworks, bringing together

stories of regional or even global scope-for example, Charles S. Maier's Leviathan 2.0: Inventing

Modern Statehood (Harvard University Press) and Jürgen Osterhammel's The Transformation

of the World: A Global History of the Nineteenth Century (Princeton University Press).

Within that literature, economic history has played a particularly important role, with trailblazing

works such as Kenneth Pomeranz's The Great Divergence: China, Europe, and the Making of the Modern

World Economy (Princeton, 2000) and Marcel van der Linden's Workers of the World: Essays

Toward a Global Labor History (Brill, 2008). Economic history, which for so long has been focused

mostly on "national" questions-the "coming of managerial capitalism" in the United States, "organized

capitalism" in Germany, the "sprouts of capitalism" in China-now increasingly tackles broader questions,

looking at capitalism as a global system.

When we apply a global perspective, we develop a new appreciation for the centrality of slavery,

in the United States and elsewhere, in the emergence of modern capitalism. We can also understand

how that dependence on slavery was eventually overcome later in the 19th century. We come to understand

that the ability of European merchants to secure ever-greater quantities of cotton cloth from South

Asia in the 17th and 18th centuries was crucial to the trans-Atlantic slave trade, as cloth came

to be the core commodity exchanged for slaves on the western coast of Africa. We grasp that the rapidly

expanding markets for South Asian cloth in Europe and elsewhere motivated Europeans to enter the

cotton-manufacturing industry, which had flourished elsewhere in the world for millennia.

And a global perspective allows us to comprehend in new ways how slavery became central to the

Industrial Revolution. As machine production of cotton textiles expanded in Britain and continental

Europe, traditional sources of raw cotton-especially cultivators in the Ottoman Empire as well as

in Africa and India-proved insufficient. With European merchants unable to encourage the monocultural

production of cotton in these regions and to transform peasant agriculture, they began to draw on

slave-grown cotton, at first from the West Indies and Brazil, and by the 1790s especially in the

United States.

As a result, Europe's ability to industrialize rested at first entirely on the control of expropriated

lands and enslaved labor in the Americas. It was able to escape the constraints on its own resources-no

cotton, after all, was grown in Europe-because of its increasing and often violent domination of

global trade networks, along with the control of huge territories in the Americas. For the first

80 years of modern industry, the only significant quantities of raw cotton entering European markets

were produced by slaves - and not from the vastly larger cotton harvests of China or India.

By 1800, 25 percent of the cotton that landed in Liverpool, the world's most important cotton

port, originated in the United States; 20 years later, that proportion had increased to 59 percent;

by 1850, 72 percent of the cotton consumed in Britain was grown in the United States, with similar

proportions for other European countries. A global perspective lets us see that the ability to secure

more and cheaper cotton gave European and North American manufacturers the ability to increase the

production of cheap yarn and cloth, which in turn allowed them to capture ancient cotton markets

in Asia, Africa, and elsewhere, furthering a wave of deindustrialization in those parts of the world.

Innovations in long-distance trade, the investment of capital over long distances, and the institutions

in which this new form of capitalist globalization were embedded all derived from a global trade

dominated by slave labor and colonial expansion.

A global perspective on the history of cotton also shows that slave labor is as much a sign of

the weakness as of the strength of Western capital and states. The ability to subdue labor in distant

locations testified to the accumulated power of European and North American capital owners. Yet it

also showed their inability to transform peasant agriculture. It was only in the last third of the

19th century that peasant producers in places such as Central Asia, West Africa, India, and upcountry

Georgia, in the United States, could be integrated into the global empire of cotton, making a world

possible in which the growing of cotton for industry expanded drastically without resort to enslaving

the world's cotton workers. Indeed, one of the weaknesses of a perspective that focuses almost exclusively

on the fabulously profitable slave/cotton complex of the antebellum American South is its inability

to explain the emergence of an empire of cotton without slavery.

We cannot know if the cotton industry was the only possible way into the modern industrial world,

but we do know that it was the path to global capitalism. We do not know if Europe and North America

could have grown rich without slavery, but we do know that industrial capitalism and the Great Divergence

in fact emerged from the violent caldron of slavery, colonialism, and the expropriation of land.

In the first 300 years of the expansion of capitalism, particularly the moment after 1780 when it

entered into its decisive industrial phase, it was not the small farmers of the rough New England

countryside who established the United States' economic position. It was the backbreaking labor of

unremunerated American slaves in places like South Carolina, Mississippi, and Alabama.

When we marshal big arguments about the West's superior economic performance, and build these

arguments upon an account of the West's allegedly superior institutions like private-property rights,

lean government, and the rule of law, we need to remember that the world Westerners forged was equally

characterized by exactly the opposite: vast confiscation of land and labor, huge state intervention

in the form of colonialism, and the rule of violence and coercion. And we also need to qualify the

fairy tale we like to tell about capitalism and free labor. Global capitalism is characterized by

a whole variety of labor regimes, one of which, a crucial one, was slavery.

During its heyday, however, slavery was seen as essential to the economy of the Western world.

No wonder The Economist worried in September 1861, when Union General John C. Frémont emancipated

slaves in Missouri, that such a "fearful measure" might spread to other slaveholding states, "inflict[ing]

utter ruin and universal desolation on those fertile territories"-and on the merchants of Boston

and New York, "whose prosperity … has always been derived" to a large extent from those territories.

Slavery did not die because it was unproductive or unprofitable, as some earlier historians have

argued. Slavery was not some feudal remnant on the way to extinction. It died because of violent

struggle, because enslaved workers continually challenged the people who held them in bondage - nowhere

more successfully than in the 1790s in the French colony of Saint-Domingue (now Haiti, site of the

first free nation of color in the New World), and because a courageous group of abolitionists struggled

against some of the dominant economic interests of their time.

A contributing factor in the death of slavery was the fact that it was a system not just of labor

exploitation but of rule that drew in particular ways on state power. Southern planters had enormous

political power. They needed it: to protect the institution of slavery itself, to expand its reach

into ever more lands, to improve infrastructures, and to position the United States within the global

economy as an exporter of agricultural commodities.

In time, the interests of the South conflicted more and more with those of a small but growing

group of Northern industrialists, farmers, and workers. Able to mobilize labor through wage payments,

Northerners demanded a strong state to raise tariffs, build infrastructures conducive to domestic

industrialization, and guarantee the territorial extension of free labor in the United States.

... ... ...

Sven Beckert is a professor of American history at Harvard University. His latest book,

Empire of Cotton: A Global History, has just been published by Alfred A. Knopf.

An interesting paper was recently published on

"Democracy in America today", and it commented in particular, on an aspect of the American prison

system. It mentioned the so-called "commercial prisons": "In the U.S. this is a thriving" business

", which operates using prison labor. One in 10 prisoners in the country is held in a commercial

prison. In 2010, two private prison corporations made about $ 3 billion in profit. This is quite

a new social phenomenon in American life and deserves to be described in more detail...

The concept and form of "prison slavery"

Commercial prisons in the United States today hold 220 thousand people behind bars. In American

literature, this phenomenon is dubbed "prison slavery". This refers to the use of prison labor. It

should be clarified: it is the use of prison labor for profit by private capital (as opposed to,

say, such work as cleaning areas and facilities in prison, or the execution of any work in the public

interest).

The privatization of prison labor in the U.S. is carried out in two main forms:

- The lending of state prison inmates as labor to private companies.

- The privatization of prison institutions, turning them into private companies of various forms

of ownership (including stock ownership).

The 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which prohibits forced labor, contains a caveat:

"Slavery and the forcible compulsion to work, except for punishment for a crime properly convicted,

shall not exist within the United States". Thus, in U.S. prisons slavery is legal.

The first of these forms ("lease" prisoners) was introduced in America in the XIX century - just

after the Civil War of 1861-1865 and the abolition of slavery, to directly eliminate the acute shortage

of cheap labor. Slaves released into freedom accused of owing their former owners or for petty crime

were sent to jail. They were then "rented out" for cotton picking, railway construction, and work

in the mines. In Georgia, for example, in the period of 1870-1910, 88% of "leased prisoners" were

Negros, in Alabama it was 93%. In Mississippi, until 1972 a huge plantation was operated that employed

prisoners under a "rental" contract. And at the beginning of XXI century, at least 37 states have

legalized the use of labor for private companies by"leasing" prisoners.

The problems of "prison slavery" in America were explored by Vicky Pelaez in the article

"The prison business in the United States: big business or a new form of slavery?"

(1) She writes: "The list of these corporations (who" lease "prisoners - VK) includes the " cream

"of the U.S. corporate community: IBM, Boeing, Motorola, Microsoft, AT & T Wireless, Texas Instruments,

Dell, Compaq, Honeywell, Hewlett-Packard, Nortel, Lucent Technologies, 3Com Intel, Northern Telecom,

TWA, Nordstrom's, Revlon, Macy's, Pierre Cardin , Target Stores, and many others. All these companies

reacted with delight to the rosy economic opportunity which prison labor promised. From 1980 to 1994,

profits (from the use of prison labor - VK) increased from 392 million to 1 billion 31 million dollars".

The benefit of this "cooperation" to private corporations is obvious: they pay "rented" slaves

the minimum wage specified in the applicable state. And in some places, even below this level. For

example, in the State of Colorado payment is about $ 2 per hour, which is much less than the minimum

wage.

The situation of some prisoners of the southern states of America is particularly difficult; where

despite the abolition of slavery in the XIX century, they continue to work on the same cotton plantations.

Of particular prominence was the maximum security prison in the state of Louisiana under the name

"Angola". The inmates of the prison process 18 thousand acres of land, on which is grown cotton,

wheat, soybeans and corn. Inmates in "Angola" receive only from 4 to 20 cents an hour for the work.

Not only that: they receive only half of the money earned, and the other half is put to the prisoners

account and paid to him at the time of his release. It is true that only a few inmates leave" Angola"

(only 3%): as most of the prisoners have long sentences, in addition they die early due to ruthless

exploitation and poor conditions.

There are other similar prison farms in Louisiana. Only 16% of prisoners in the State are sentenced

to agricultural works. In neighboring states - Texas and Arkansas - the proportion of prisoners is

17% and 40%.

The second form of "prison slavery" - private prisons - appeared in the U.S. in the 1980s under

President Reagan, and then continued with the privatization of state prisons under Presidents George

Bush Senior and Bill Clinton. The first privatization of a state prison in Tennessee occurred in

February 1983, by venture capital firm Massey Burch Investment.

The Prison-industrial complex

According to Vicky Pelaez, in the U.S. by 2008, 27 states already had 100 private prisons holding

62 thousand prisoners (for comparison, 10 years previously there five private prison holding two

thousand prisoners). These prisons are operated by 18 private corporations. The largest of them are

the Correctional Corporation of America (CCA) and G4S: they controlled 75% of all private prison

inmates. In 1986 shares of CCA began trading on the New York Stock Exchange. In 2009, its market

capitalization was estimated at 2.26 billion dollars.

Private prison companies conclude long-term concession agreements with the government in the management

of prisons. In this case, they get some money from the state for each prisoner. Payment for work

done by the prisoner is determined by the company themselves, and rates are much lower than the amount

paid by businesses that operate on a rental basis (which was the first form of "prison slavery").

Pay rates in private prisons sometimes equal 17 cents per hour. Even for the most skilled labor the

pay is no more than 50 cents. In prison, in contrast to industrial companies, there can be no talk

of a strike, trade union activities, holidays, or sickness. To "encourage prison slaves" to work

the employers promise "early release for good work". However, it applies a system of fines, which

can actually lead to life imprisonment.

The U.S. prison industry is based both on the direct use of prisoners labor by private capital

(either "leased" or direct operation of private prisons), and indirectly. Indirectly mean that the

organization of production is carried out by the prison authorities and the products manufactured

by the prisoners are supplied under contract to private companies. The prices of these products are

usually much lower than the market price. It is difficult to determine the extent of indirect use

of prison labor by private companies in the USA. Here you can find a lot of abuse on the basis of

the collusion between state prison administrations and private companies. This kind of business is

usually known as "shadow business".

According to the American press, "the prison-industrial complex" began to form based on

private prisons. It became prominent in the production of many products in the U.S. Today, the U.S.

prison industry produces 100% of all military helmets, uniforms, belts and shoulder belts, vests,

ID cards, shirts, pants, tents, backpacks and flasks for the country`s army. In addition to military

equipment and uniforms, prisons produce 98% of the market in installation tools, 46% of bulletproof

vests, 36% of home appliances, 30% of headphones, microphones, megaphones, and 21% of office furniture,

aircraft and medical equipment, and many more.

In the Vicky Pelaez article we read: "The prison industry is one of the fastest growing industries,

and its investors are on Wall Street". Referring to another source, the same author writes: "This

multi-million dollar industry has its own trade exhibitions, conventions, websites, and online catalogues.

It has direct advertising campaigns, has design and construction firms, investment funds on Wall

Street ,building maintenance firms, food supply companies, it has armed security, and soundproofed

rooms".

The rate of profit in the prison industry in the U.S. is very high. In connection with

this, transnational corporations (TNCs) no longer have the incentive to transfer their production

from the U.S. to economically backward countries. It is even possible that the process can go in

the opposite direction. Vicky Pelaez says: "Thanks to prison labor the United States was

again an attractive location for investment in work that used to be the lot of the Third World. In

Mexico, an assembly plant which was located

near the border was closed and its operations moved to "Saint-Quentin" prison (California). In

Texas, a factory fired 150 workers and contracted with private prisons, "Lockhart", which makes parts

for electrical companies such as IBM and Compaq. The Representative for the State of Oregon recently

asked the Nike corporation to hasten the transfer of production from Indonesia to Oregon, saying

that "here the manufacturer will not have problems with transportation, here we will provide competitive

prison labor".

Greed as a factor in the growth of the American Gulag

American business started to feel that the use of their own "prison slaves" was a "gold mine".

Accordingly, the largest U.S. corporations began to delve into how to format a continent of inmates

in U.S. prisons and do everything possible to ensure that there were as many prisoners as possible.

We believe that it was the interests of corporate business that contributed to the fact that

the number of prisoners in the U.S. grew rapidly. To again quote Vicky Pelaez: "Private

hire of prisoners provokes the desire to put more people in jail. Prisons depend on income. Corporate

stockholders who make money from the labor of prisoners lobbied for longer sentence periods, to provide

themselves with labor. "The system feeds itself", said the study of the Progressive Labor Party,

which believes the prison system is", an imitation of Nazi Germany in

regard to forced slave labor and concentration camps".

However, even in state prisons, the use of prison labor by the authorities is profitable. In state

prisons prison labor rates are higher than in private prisons. Inmates receive $2 - $ 2.5 per hour

(excluding overtime). However, state prisons are actually "self-financing": half of the prisoners

earnings are taken from them to pay for "rent" for their room and food.

So talk about state prisons in the United States being a "burden" on the country's budget, are simply

an excuse to justify their transfer to private hands.

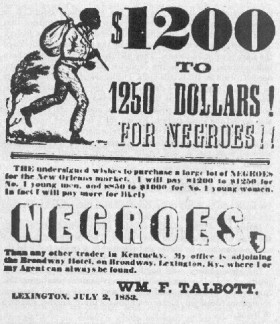

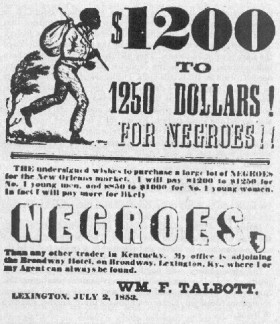

Slavery is not new to America. It was the year 1619 when the first African slaves arrived in Virginia.

Allow for just a moment for the reality of that situation to sink in. Men, women and children were

involuntarily uprooted from their homes, violently packed onto a ship like canned sardines and taken

to a new land where they would be worked to the bone day after day.

Over the next 250 years, America would see many slaves step onto its soil. The US Constitution would

make slavery illegal in the Northwest Territory in 1787 but Congress would not ban the slave trade

until 1808. The demand for slave labor sky rocketed at the invention of Eli Whitney's cotton gin

in 1793. Those who tried to revolt were hanged. Those who tried to escape and were caught were returned

to their slave master per a federal law. In 1863 President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation

declaring "that all persons held as slaves" within the Confederate state "are, and henceforward shall

be free." Two years later the thirteenth amendment abolishes slavery throughout the United States.

However, it would be 2 months before slaves in Texas heard the news they had been freed.

"It has been called by a great many names and it will call itself by yet another, and all of us

had better wait and see what new form this old monster will assume." –Frederick Douglass

If you read my last column, the first of a series on

slavery in America,

you know that there are approximately 1 million slaves in America today.* Oh sure, the thirteenth

amendment did declare the end to all slavery in 1865, but in the 150 years since, the slave trade

has grown like a pesky little weed throughout the United States. Next to the largest industry in

the world, drug trafficking, human trafficking is the second largest industry, closely followed by

arms trafficking.

The quote above, of activist and leader Frederick Douglass, is disturbingly true. We might not see

Africans picking cotton in the south anymore and we might have an emancipation proclamation, declaring

freedom for all men, women and children, but today we find ourselves further immersed in a culture

of slavery than when Lincoln gave his speech.

So if slavery today doesn't look like it did 150 years ago, what does it look like now?

At the core, slavery is the buying and selling of human beings. Slavery is involuntary subjection

to another or others. Unlike drugs, people can be sold over and over again. The average cost for

a human being around the world is roughly $50 USD.

The root of slavery is buried in deep, dark soil. The root is nourished by a demand and as that

demand increases, the root breaks through the surface, spreading like wild weeds destroying everything

in its path. It is the demand for slaves that has changed over time, giving shape to a number of

types of slavery that exist today.

Sex trafficking is the most known form of modern day slavery. Obviously, the demand for this type

of slavery is sex. Often we think of sex trafficking happening in Southeast Asia or on the crowded

streets of Calcutta. But don't be fooled. The demand for sex, mostly for young girls, is happening

across America. Just today, Superbowl Sunday,

CNN ran an article about Miami's recent peak of sex trafficking to meet the demands for sex from

those traveling to Miami for the game. There is much discussion on the issue of sex slavery and prostitution.

Check back for an upcoming post on this issue. Sex slavery is not confined to street corners or dark

alleys. Brothels exist behind restaurants, massage and nail parlors, motels and small businesses.

Labor trafficking is another form of slavery happening right here in America. Labor trafficking is

the recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, or obtaining of a person for labor or services,

through the use of force, fraud, or coercion for the purpose of subjection to involuntary servitude,

peonage, debt bondage or slavery.**

In the first column in this series, referenced above, I mentioned I had the privilege of hearing

a survival story of a young woman who had been trafficked into Orange County. This young woman was

only a child when she was brought to America and forced to work as a domestic slave and caregiver

to the other children in the home. She slept in the garage without light or access to the outside

and where field mice frequented her. Last week I heard another woman share her story of being brought

to US and sold to work as a domestic slave, caring for 4 homes and several children. She was a child

herself at the time and was enslaved to this large family for 7 years. This is happening to other

children across the United States.

As I mentioned above, slavery is not new to America. Slavery is not new to the world. Slavery is

not new to God. As this series on HT continues, I'll write about what we know of God's character

and response to HT by taking a look at what the Bible tells us. The idea of a person being bought

and sold over and over again angers me. I think it angers God too. Keep checking back about once

a week and you'll see why I think this.

Also in future columns, I'll be addressing the issue of demand for slavery and what you and I can

do about diminishing it.

In the last post and here I have mentioned a few of the areas I'll be writing on in regards to HT

in America. I would like to hear from you on this as well. Are there areas of HT that you'd like

me to research and write about? Do you have questions about modern day slavery? Whatever it is, I'd

love to hear from you. ConversantLife.com is a place where we can have discussions about tough issues

like this and really learn from one another. I welcome your thoughts.

If you know of someone who meets one of the types of HT mentioned above, the national number to call

is (888) 373-7888. It's an easy one to memorize and even easier to put into your cell phone. If ever

you have a suspicion of trafficking, do not hesitate to call. You may be saving someone's life by

doing so.

*Victims of crimes such as trafficking and violence don't often speak up about the crimes committed

against them due to fear placed upon them by their abuser, therefore making this number hard to pinpoint

as exact.

**Definition taken from

Live2free.org website.

About 100,000 girls in the U.S. are under the control of a pimp or trafficker, Shared Hope Intermational

says.

February 6, 2010 |

CNN.com

Volunteers try to dissuade young sex workers on Super Bowl weekend

, CNN

8:52 p.m. EST

About 100,000 girls in the U.S. are under the control of a pimp or trafficker, Shared Hope

Intermational says.

STORY HIGHLIGHTS

Sex workers out in force in Miami on Super Bowl weekend, advocacy groups say

Many of them are underage, and brought in from other states

Many of the sex workers are runaways who were abused

Volunteers are hitting the streets, reaching out to young girls

RELATED TOPICS

Human Trafficking

Super Bowl

Miami

(CNN) -- Volunteers are taking to the streets of Miami, Florida, this Super Bowl weekend to inform

teenage girls of alternatives to working as prostitutes.

Just as Miami's hotels, restaurants and retail stores are seeing a bump in business for one of the

biggest sporting events of the year, law enforcement and social service agencies say they are also

witnessing a spike in trafficking of underage sex workers.

"Many social service agencies and law enforcement agencies recognize that there was an increase of

victims of trafficking during last year's Super Bowl," said Regina Bernadin, Statewide Human Trafficking

Coordinator for the Florida Department of Children and Families.

"That correlates with research that whenever there's a convention, a concert or a large event, traffickers

will bring girls to the area to serve the influx of visitors," she added.

Girls and young women, as well as their pimps, come from as far as New York and Texas to meet the

increased demand, says Brad Dennis, director of search operations for KlaasKIDS Foundation, which

is spearheading the outreach effort.

"It's just that party culture," Dennis said. "Super Bowl is an entertainment event and everyone wants

to come down and party and when you throw that mix into an area with lots money to spend, it's a

traffickers' playground."

Due to the clandestine nature of underage sex trafficking, it's hard to track the exact number of

girls who are brought in for the Super Bowl and other big events. But a look at online escort listings

gives some clues, Dennis said.

One free online site offered 38 ads for Miami on January 16, but more than 200 on Saturday night,

he said. It was impossible to tell how many of the advertised escorts might be underage.

On less high-profile weekends in Miami, Trudy Novicki, Executive Director of Kristi House, said her

organization looks at the number of reported runaways as an indicator of how many girls could be

working in the sex trade.

"We know that a very high percentage of runaways will end up being approached by a pimp within 72

hours of hitting the streets and they will be prostituted in order to survive on the streets," Novicki

said. "So we know there is an extremely high correlation between runaway juveniles and underage prostitution.

Kristi House is also helping to coordinate the Super Bowl weekend outreach, Novicki said.

The profile of a typical runaway cuts across socio-economic lines, Novicki said, but many of them

leave home to escape some form of abuse.

In an effort to reach those girls, state and local law enforcement agencies are teaming up with social

service agencies to coordinate nighttime outreaches to girls on the streets.

Starting Wednesday, small teams of three or four volunteers have set out each night scoping the streets

for potential trafficking victims, covering ground from Fort Lauderdale to South Beach to Hialeah.

The hard part isn't locating the girls but finding an opportunity to approach them without drawing

the attention of their pimps, said volunteer Eddy Ameen.

"Safety's always an issue because we know the girls aren't alone. We have to make sure we're not

presenting potential harm to them," said Ameen, executive director of StandUp For Kids Miami.

If they get a girl's attention, they hand her a card with a hot line number for resources on how

to get out of "the life," Ameen said.

"It's usually a very brief encounter -- just a few minutes, if that. Some may not call the next day

or the day after or ever. We can give out card 100 times and maybe five will call. But if they do,

we've made a difference," he added.

Another component of the operation aims to educate hotels and the hospitality industry on how to

spot sex-trafficking operations on their premises and report it -- an approach that yielded the majority

of leads at last year's Super Bowl in Tampa, Florida, according to Dennis.

"Last year we put together 21 leads that we gave to law enforcement, most of them from business owners

or hotel owners basically stating I believe I have a trafficker and his girls stay at my hotel,"

he said.

"They'd see a lot of traffic coming and going, or girls standing out on corners.," Dennis added.

"Those are all obvious signs, but good on them for actually reporting it."

The epidemic of underage sex trafficking isn't contained to Super Bowl weekend. An estimated 100,000

girls in the United States are under the control of a pimp or trafficker, according to Shared Hope

Intermational, a nonprofit that works to combat worldwide sex trafficking.

It's a reality that groups like KlaasKIDS, StandUp For Kids and Kristi House encounter daily, Ameen

said.

"The common perception is that the girls enjoy it, they make money, they're independent or they do

it by choice. But when you work with young people selling their bodies, it's not a choice. It's a

way to survive," he said.

"I don't want the idea to go away when Super Bowl ends. The reality is that it's more concentrated

on Super Bowl weekend, but they're still out there come Monday morning."

Softpanorama Recommended

...

Human

Trafficking Modern-Day Slavery in America WGBH News

Human Trafficking

Polaris Combating Human Trafficking and Modern-day Slavery

BBC - Ethics

- Slavery Modern slavery

Slavery in America New Forms of an Old Monster conversantlife.com

Volunteers try to dissuade young sex workers on Super Bowl weekend - CNN.com

Society

Groupthink :

Two Party System

as Polyarchy :

Corruption of Regulators :

Bureaucracies :

Understanding Micromanagers

and Control Freaks : Toxic Managers :

Harvard Mafia :

Diplomatic Communication

: Surviving a Bad Performance

Review : Insufficient Retirement Funds as

Immanent Problem of Neoliberal Regime : PseudoScience :

Who Rules America :

Neoliberalism

: The Iron

Law of Oligarchy :

Libertarian Philosophy

Quotes

War and Peace

: Skeptical

Finance : John

Kenneth Galbraith :Talleyrand :

Oscar Wilde :

Otto Von Bismarck :

Keynes :

George Carlin :

Skeptics :

Propaganda : SE

quotes : Language Design and Programming Quotes :

Random IT-related quotes :

Somerset Maugham :

Marcus Aurelius :

Kurt Vonnegut :

Eric Hoffer :

Winston Churchill :

Napoleon Bonaparte :

Ambrose Bierce :

Bernard Shaw :

Mark Twain Quotes

Bulletin:

Vol 25, No.12 (December, 2013) Rational Fools vs. Efficient Crooks The efficient

markets hypothesis :

Political Skeptic Bulletin, 2013 :

Unemployment Bulletin, 2010 :

Vol 23, No.10

(October, 2011) An observation about corporate security departments :

Slightly Skeptical Euromaydan Chronicles, June 2014 :

Greenspan legacy bulletin, 2008 :

Vol 25, No.10 (October, 2013) Cryptolocker Trojan

(Win32/Crilock.A) :

Vol 25, No.08 (August, 2013) Cloud providers

as intelligence collection hubs :

Financial Humor Bulletin, 2010 :

Inequality Bulletin, 2009 :

Financial Humor Bulletin, 2008 :

Copyleft Problems

Bulletin, 2004 :

Financial Humor Bulletin, 2011 :

Energy Bulletin, 2010 :

Malware Protection Bulletin, 2010 : Vol 26,

No.1 (January, 2013) Object-Oriented Cult :

Political Skeptic Bulletin, 2011 :

Vol 23, No.11 (November, 2011) Softpanorama classification

of sysadmin horror stories : Vol 25, No.05

(May, 2013) Corporate bullshit as a communication method :

Vol 25, No.06 (June, 2013) A Note on the Relationship of Brooks Law and Conway Law

History:

Fifty glorious years (1950-2000):

the triumph of the US computer engineering :

Donald Knuth : TAoCP

and its Influence of Computer Science : Richard Stallman

: Linus Torvalds :

Larry Wall :

John K. Ousterhout :

CTSS : Multix OS Unix

History : Unix shell history :

VI editor :

History of pipes concept :

Solaris : MS DOS

: Programming Languages History :

PL/1 : Simula 67 :

C :

History of GCC development :

Scripting Languages :

Perl history :

OS History : Mail :

DNS : SSH

: CPU Instruction Sets :

SPARC systems 1987-2006 :

Norton Commander :

Norton Utilities :

Norton Ghost :

Frontpage history :

Malware Defense History :

GNU Screen :

OSS early history

Classic books:

The Peter

Principle : Parkinson

Law : 1984 :

The Mythical Man-Month :

How to Solve It by George Polya :

The Art of Computer Programming :

The Elements of Programming Style :

The Unix Hater’s Handbook :

The Jargon file :

The True Believer :

Programming Pearls :

The Good Soldier Svejk :

The Power Elite

Most popular humor pages:

Manifest of the Softpanorama IT Slacker Society :

Ten Commandments

of the IT Slackers Society : Computer Humor Collection

: BSD Logo Story :

The Cuckoo's Egg :

IT Slang : C++ Humor

: ARE YOU A BBS ADDICT? :

The Perl Purity Test :

Object oriented programmers of all nations

: Financial Humor :

Financial Humor Bulletin,

2008 : Financial

Humor Bulletin, 2010 : The Most Comprehensive Collection of Editor-related

Humor : Programming Language Humor :

Goldman Sachs related humor :

Greenspan humor : C Humor :

Scripting Humor :

Real Programmers Humor :

Web Humor : GPL-related Humor

: OFM Humor :

Politically Incorrect Humor :

IDS Humor :

"Linux Sucks" Humor : Russian

Musical Humor : Best Russian Programmer

Humor : Microsoft plans to buy Catholic Church

: Richard Stallman Related Humor :

Admin Humor : Perl-related

Humor : Linus Torvalds Related

humor : PseudoScience Related Humor :

Networking Humor :

Shell Humor :

Financial Humor Bulletin,

2011 : Financial

Humor Bulletin, 2012 :

Financial Humor Bulletin,

2013 : Java Humor : Software

Engineering Humor : Sun Solaris Related Humor :

Education Humor : IBM

Humor : Assembler-related Humor :

VIM Humor : Computer

Viruses Humor : Bright tomorrow is rescheduled

to a day after tomorrow : Classic Computer

Humor

The Last but not Least Technology is dominated by

two types of people: those who understand what they do not manage and those who manage what they do not understand ~Archibald Putt.

Ph.D

Copyright © 1996-2021 by Softpanorama Society. www.softpanorama.org

was initially created as a service to the (now defunct) UN Sustainable Development Networking Programme (SDNP)

without any remuneration. This document is an industrial compilation designed and created exclusively

for educational use and is distributed under the Softpanorama Content License.

Original materials copyright belong

to respective owners. Quotes are made for educational purposes only

in compliance with the fair use doctrine.

FAIR USE NOTICE This site contains

copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically

authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available

to advance understanding of computer science, IT technology, economic, scientific, and social

issues. We believe this constitutes a 'fair use' of any such

copyrighted material as provided by section 107 of the US Copyright Law according to which

such material can be distributed without profit exclusively for research and educational purposes.

This is a Spartan WHYFF (We Help You For Free)

site written by people for whom English is not a native language. Grammar and spelling errors should

be expected. The site contain some broken links as it develops like a living tree...

Disclaimer:

The statements, views and opinions presented on this web page are those of the author (or

referenced source) and are

not endorsed by, nor do they necessarily reflect, the opinions of the Softpanorama society. We do not warrant the correctness

of the information provided or its fitness for any purpose. The site uses AdSense so you need to be aware of Google privacy policy. You you do not want to be

tracked by Google please disable Javascript for this site. This site is perfectly usable without

Javascript.

Last modified:

February, 09, 2021

If

you think that slavery disappeared in the USA think again. Slaves now are cheaper than ever and can

generate high economic returns.

Invisible

hand of the market proved to be pretty adept in reproducing slavery. About 100,000 girls

in the U.S. are under the control of a pimp or trafficker, Shared Hope International says. Modern

slavery is very cheap, and Kevin Bales has argued that this has made modern slavery even worse than

that of Atlantic Slave Trade:

If

you think that slavery disappeared in the USA think again. Slaves now are cheaper than ever and can

generate high economic returns.

Invisible

hand of the market proved to be pretty adept in reproducing slavery. About 100,000 girls

in the U.S. are under the control of a pimp or trafficker, Shared Hope International says. Modern

slavery is very cheap, and Kevin Bales has argued that this has made modern slavery even worse than

that of Atlantic Slave Trade: Iowa

radio host and influential conservative kingmaker Jan Mickelson unveiled an

immigration plan that would make undocumented immigrants who don't leave the country

after an allotted time "property of the state," asking, "What's wrong with slavery?"

when a caller criticized his plan.

Iowa

radio host and influential conservative kingmaker Jan Mickelson unveiled an

immigration plan that would make undocumented immigrants who don't leave the country

after an allotted time "property of the state," asking, "What's wrong with slavery?"

when a caller criticized his plan.