Supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) is an

abnormally fast

heart rhythm arising from improper

electrical activity in upper part of the heart.[1]

There are four main types:

atrial fibrillation,

paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (PSVT),

atrial

flutter, and

Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome.[1]

Symptoms may include

palpitations,

feeling faint, sweating,

shortness of breath, or

chest pain.[2]

They start from either the

atria

or

atrioventricular node.[1]

They are generally due to one of two mechanisms:

re-entry or

increased automaticity.[3]

The other type of fast heart rhythm are

ventricular arrhythmias—rapid rhythms that start within the

ventricle.[1]

Diagnosis is typically by

electrocardiogram (ECG),

holter

monitor, or

event monitor.

Blood tests may be done to rule out specific underlying causes such as

hyperthyroidism or

electrolyte abnormalities.[4]

Specific treatments depend on the type of SVT. They can include medications, medical

procedures, or surgery.

Vagal maneuvers or a procedure known as

catheter ablation may be effective in certain types. For atrial fibrillation

calcium channel blockers or

beta blockers may be used.

Long term some people benefit from

blood thinners such as

aspirin or

warfarin.[5]

Atrial fibrillation affects about 25 per 1000 people,[6]

paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia 2.3 per 1000,[7]

Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome 2 per 1000,[8]

and atrial flutter 0.8 per 1000.[9]

Signs and symptoms[edit]

Signs and symptoms can arise suddenly and may resolve without treatment. Stress,

exercise, and emotion can all result in a normal or physiological increase in heart

rate, but can also, more rarely, precipitate SVT. Episodes can last from a few minutes

to one or two days, sometimes persisting until treated. The rapid heart rate reduces the

opportunity for the "pump" to fill between beats decreasing

cardiac

output and as a consequence

blood

pressure. The following symptoms are typical with a rate of 150–270 or more beats

per minute:

For infants and toddlers, symptoms of heart arrhythmias such as SVT are more

difficult to assess because of limited ability to communicate. Caregivers should watch

for lack of interest in feeding, shallow breathing, and lethargy. These symptoms may be

subtle and may be accompanied by vomiting and/or a decrease in responsiveness.[10]

Diagnosis[edit]

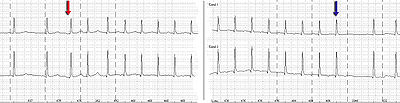

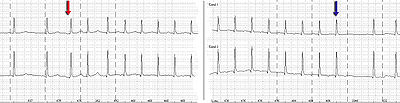

Holter monitor-Imaging with start (red arrow) and end (blue arrow) of a SV-tachycardia

with a pulse frequency of about 128/min.

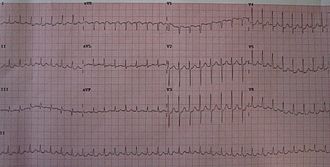

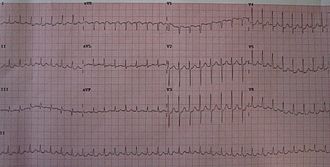

A 12-lead ECG showing paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia at about 180

beats per minute.

Subtypes of SVT can usually be distinguished by their

electrocardiogram (ECG) characteristics

Most have a narrow

QRS complex,

although, occasionally, electrical conduction abnormalities may produce a wide QRS

complex that may mimic

ventricular tachycardia (VT). In the clinical setting, the distinction between

narrow and wide complex tachycardia (supraventricular vs. ventricular) is fundamental

since they are treated differently. In addition, ventricular tachycardia can quickly

degenerate to

ventricular fibrillation and

death and merits

different consideration.

In the less common situation in which a wide-complex tachycardia may actually be

supraventricular, a number of

algorithms have

been devised to assist in distinguishing between them.[11]

In general, a history of structural heart disease markedly increases the likelihood that

the tachycardia is ventricular in origin.

-

Sinus tachycardia is physiologic or "appropriate" when a reasonable stimulus,

such as the

catecholamine surge associated with fright, stress, or physical activity,

provokes the tachycardia. It is identical to a

normal sinus rhythm except for its faster rate (>100 beats per minute in adults).

Sinus tachycardia is considered by most sources to be an SVT.

- Sinoatrial node reentrant tachycardia (SANRT) is caused by a

reentry circuit localised to the SA node, resulting in a

P-wave of normal shape and size (morphology)

that falls before a regular, narrow QRS complex. It cannot be distinguished

electrocardiographically from sinus tachycardia unless the sudden onset is observed

(or recorded on a

continuous monitoring device). It may sometimes be distinguished by its prompt

response to

vagal

maneuvers.

- Ectopic (unifocal)

atrial tachycardia arises from an independent focus within the atria,

distinguished by a consistent P-wave of abnormal shape and/or size that falls before

a narrow, regular QRS complex. It is caused by automaticity, which means that

some cardiac muscle cells, which have the primordial (primitive, inborn, inherent)

ability to generate electrical impulses that is common to all cardiac muscle cells,

have established themselves as a 'rhythm center' with a natural rate of electrical

discharge that is faster than the normal SA node.

-

Multifocal atrial tachycardia (MAT) is tachycardia arising from at least three

ectopic foci within the atria, distinguished by P-waves of at least three different

morphologies that all fall before irregular, narrow QRS complexes.

Atrial fibrillation: Red dots show atrial fibrillation activity.

-

Atrial fibrillation meets the definition of SVT when associated with a

ventricular response greater than 100 beats per minute. It is characterized as an

"irregularly irregular rhythm" both in its atrial and ventricular depolarizations and

is distinguished by its fibrillatory atrial waves that, at some point in their chaos,

stimulate a response from the ventricles in the form of irregular, narrow QRS

complexes.

-

Atrial flutter, is caused by a re-entry rhythm in the atria, with a regular

atrial rate often of about 300 beats per minute. On the ECG this appears as a line of

"sawtooth" waves preceding the QRS complex. The AV node will not usually conduct 300

beats per minute so the P:QRS ratio is usually 2:1 or 4:1 pattern, (though rarely

3:1, and sometimes 1:1 where class IC

antiarrhythmic drug are in use). Because the ratio of P to QRS is usually

consistent, A-flutter is often regular in comparison to its irregular counterpart,

atrial fibrillation. Atrial flutter is also not necessarily a tachycardia unless the

AV node permits a ventricular response greater than 100 beats per minute.

-

AV nodal reentrant tachycardia (AVNRT) involves a reentry circuit forming next

to, or within, the AV node. The circuit most often involves two tiny pathways one

faster than the other. Because the node is immediately between the atria and

ventricle, the re-entry circuit often stimulates both, appearing as a backward

(retrograde) conducted P-wave buried within or occurring just after the

regular, narrow QRS complexes.

-

Atrioventricular reciprocating tachycardia (AVRT), also results from a reentry

circuit, although one physically much larger than AVNRT. One portion of the circuit

is usually the AV node, and the other, an abnormal accessory pathway (muscular

connection) from the atria to the ventricle.

Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome is a relatively common abnormality with an

accessory pathway, the

bundle of Kent crossing the

AV valvular ring.

- In orthodromic AVRT, atrial impulses are conducted down through the AV node

and retrogradely re-enter the atrium via the accessory pathway. A distinguishing

characteristic of orthodromic AVRT can therefore be a P-wave that follows each of

its regular, narrow QRS complexes, due to retrograde conduction.

- In antidromic AVRT, atrial impulses are conducted down through the accessory

pathway and re-enter the atrium retrogradely via the AV node. Because the

accessory pathway initiates conduction in the ventricles outside of the

bundle

of His, the QRS complex in antidromic AVRT is often wider than usual, with a

delta wave.

- Finally,

junctional ectopic tachycardia (JET) is a rare tachycardia caused by increased

automaticity of the AV node itself initiating frequent heart beats. On the ECG,

junctional tachycardia often presents with abnormal morphology P-waves that may fall

anywhere in relation to a regular, narrow QRS complex. It is often due to drug

toxicity.

Classification[edit]

Impulse arising in

SA node, traversing atria to

AV node, then entering ventricle. Rhythm originating at or above AV node

constitutes SVT.

Atrial fibrillation: Irregular impulses reaching AV node, only some being

transmitted.

The following types of supraventricular tachycardias are more precisely classified by

their specific site of origin. While each belongs to the broad classification of SVT,

the specific term/diagnosis is preferred when possible:

Sinoatrial origin:

- Sinoatrial nodal reentrant tachycardia (SNRT)

Atrial

origin:

- (Without rapid ventricular response, fibrillation and flutter are usually not

classified as SVT)

Atrioventricular origin (junctional tachycardia):

Pathophysiology[edit]

The main pumping chamber, the

ventricle, is protected (to a certain extent) against excessively high rates arising

from the supraventricular areas by a "gating mechanism" at the

atrioventricular node, which allows only a proportion of the fast impulses to pass

through to the ventricles.

In

Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, a "bypass tract" avoids this node and its protection

and the fast rate may be directly transmitted to the ventricles. This situation has

characteristic findings on

ECG.

Treatment[edit]

Most SVTs are unpleasant rather than life-threatening, although very fast heart

rates can be problematic for those with underlying

ischemic heart disease or the elderly.

Episodes require treatment when they occur, but interval therapy may also be used to

prevent or reduce recurrence. While some treatment modalities can be applied to all SVTs,

there are specific therapies available to treat some sub-types. Effective treatment

consequently requires knowledge of how and where the arrhythmia is initiated and its

mode of spread.

SVTs can be classified by whether the AV node is involved in maintaining the rhythm.

If so, slowing conduction through the AV node will terminate it. If not, AV nodal

blocking maneuvers will not work, although transient AV block is still useful as it may

unmask an underlying abnormal rhythm.

Prevention[edit]

Once an acute arrhythmia has been terminated, ongoing treatment may be indicated to

prevent recurrence. However, those that have an isolated episode, or infrequent and

minimally symptomatic episodes, usually do not warrant any treatment other than

observation.

In general, patients with more frequent or disabling symptoms warrant some form of

prevention. A variety of drugs including simple AV nodal blocking agents such as

beta-blockers and

verapamil, as

well as anti-arrhythmics may be used, usually with good effect, although the risks of

these therapies need to be weighed against potential benefits.

Radiofrequency ablation has revolutionized the treatment of tachycardia caused by a

re-entrant pathway. This is a low-risk procedure that uses a catheter inside the heart

to deliver radio frequency energy to locate and destroy the abnormal electrical

pathways. Ablation has been shown to be highly effective: around 90% in the case of

AVNRT. Similar high rates of success are achieved with AVRT and typical atrial flutter.

Cryoablation is a newer treatment for SVT involving the AV node directly. SVT

involving the AV node is often a contraindication for using radiofrequency ablation due

to the small (1%) incidence of injuring the AV node, requiring a permanent pacemaker.

Cryoablation uses a catheter supercooled by nitrous oxide gas freezing the tissue to

−10 °C. This provides the same result as radiofrequency ablation but does not carry the

same risk. If you freeze the tissue and then realize you are in a dangerous spot, you

can halt freezing the tissue and allow the tissue to spontaneously rewarm and the tissue

is the same as if you never touched it. If after freezing the tissue to −10 °C you get

the desired result, then you freeze the tissue down to a temperature of −73 °C and you

permanently ablate the tissue.

This therapy has further improved the treatment options for people with AVNRT (and

other SVTs with pathways close to the AV node), widening the application of curative

ablation to young patients with relatively mild but still troublesome symptoms who would

not have accepted the risk of requiring a pacemaker.

Notable cases[edit]

After being successfully diagnosed and treated,

Bobby Julich

went on to place third in the

1998 Tour de France and win a Bronze Medal in the

2004 Summer Olympics. Women's Olympic

volleyball

player

Tayyiba Haneef-Park underwent an

ablation

for SVT just two months before competing in the

2008 Summer Olympics.[12]

Tony Blair,

former PM of the UK, was also operated on for

atrial

flutter.

Anastacia was

diagnosed with the disease.[13]

Women's Olympic gold medalist swimmers,

Rebecca Soni

and Dana

Vollmer have both had heart surgery to correct SVT. In addition, Neville Fields had

corrective surgery for SVT in early 2006. Wrestling manager

Paul Bearer's

heart attack was attributed to SVT, resulting in his death.[14]

Nathan Cohen, New Zealand's two-time world champion and Olympic champion rower, was

diagnosed with SVT in 2013 when he was 27 years old.[15][16][17]

References[edit]

- ^

Jump up to: a

b

c

d

"Types of Arrhythmia". NHLBI. July 1, 2011.

-

Jump up ^

"What Are the Signs and Symptoms of an Arrhythmia?". NHLBI. July 1,

2011. Retrieved 27

September 2016.

-

Jump up ^

Al-Zaiti, SS; Magdic,

KS (September 2016). "Paroxysmal Supraventricular Tachycardia: Pathophysiology,

Diagnosis, and Management.". Critical care nursing clinics of North America.

28 (3): 309–16.

PMID 27484659.

-

Jump up ^

"How Are Arrhythmias Diagnosed?". NHLBI. July 1, 2011.

-

Jump up ^

"How Are Arrhythmias Treated?". NHLBI. July 1, 2011.

Retrieved 27 September 2016.

-

Jump up ^

Zoni-Berisso, M;

Lercari, F; Carazza, T; Domenicucci, S (2014). "Epidemiology of atrial

fibrillation: European perspective.". Clinical epidemiology. 6:

213–20.

doi:10.2147/CLEP.S47385.

PMID 24966695.

-

Jump up ^

Katritsis, Demosthenes

G.; Camm, A. John; Gersh, Bernard J. (2016).

Clinical Cardiology: Current Practice Guidelines. Oxford University

Press. p. 538.

ISBN 9780198733324.

-

Jump up ^

Ferri, Fred F. (2016).

Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2017: 5 Books in 1. Elsevier Health Sciences.

p. 1372.

ISBN 9780323448383.

-

Jump up ^

Bennett, David H. (2012).

Bennett's Cardiac Arrhythmias: Practical Notes on Interpretation and Treatment.

John Wiley & Sons. p. 49.

ISBN 9781118432402.

-

Jump up ^

Iyer, V. Ramesh, MD, MRCP.

"Supraventricular Tachycardia". Children's Hospital of Philadelphia.

Retrieved June 8, 2014.

-

Jump up ^

Lau EW, Ng GA (2002).

"Comparison of the performance of three diagnostic algorithms for regular broad

complex tachycardia in practical application". Pacing and Clinical

Electrophysiology. 25 (5): 822–7.

doi:10.1046/j.1460-9592.2002.00822.x.

PMID 12049375.

-

Jump up ^

"USA Volleyball 2008 Olympic Games Press Kit"

(PDF). Usavolleyball.org. Retrieved

2013-11-02.

-

Jump up ^

"Anastacia delays heart surgery".

News

of the World. 3 Nov 2008. Retrieved

30 Apr 2010.

-

Jump up ^

"Paul Bearer Cause of Death – Heart Attack". TMZ.com. 2013-03-23.

Retrieved 2013-11-02.

-

Jump up ^

Ian Anderson (27 August

2013).

"Rowing | Bad day for New Zealand crews". Stuff.co.nz.

Retrieved 30 October 2013.

-

Jump up ^

"Heart problems force Olympic champion out of world champs". Radio New

Zealand. 26 August 2013. Retrieved

30 October 2013.

-

Jump up ^

"Heart trouble rules Cohen out of rowing World Champs". TVNZ. 26 August 2013.

Retrieved 30 October 2013.

Scott Brady of punk band Brave The Wild (https://www.facebook.com/BraveTheWild)

suffers from this. He had his first attack on April 9, 2012 while golfing and was

hospitalized over night. He was diagnosed April 17, 2014 in Hamilton ON after

having an attack walking home from dinner on March 16, 2014.

External links[edit]